Africa Sees Decreased Off-Continent Irregular Migration

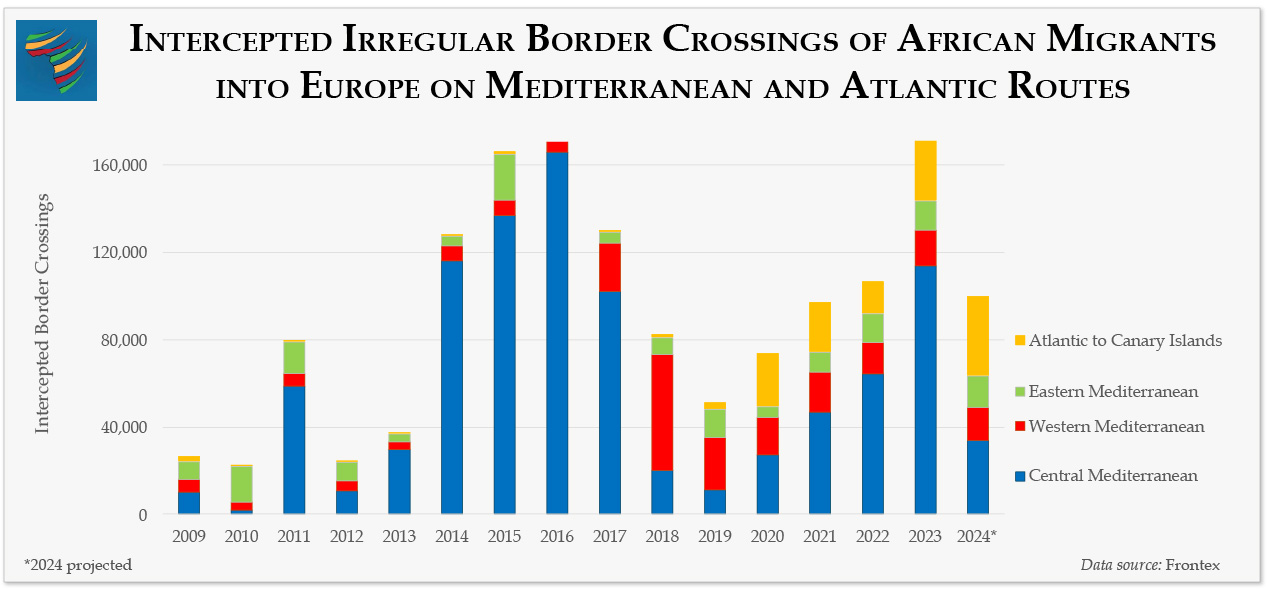

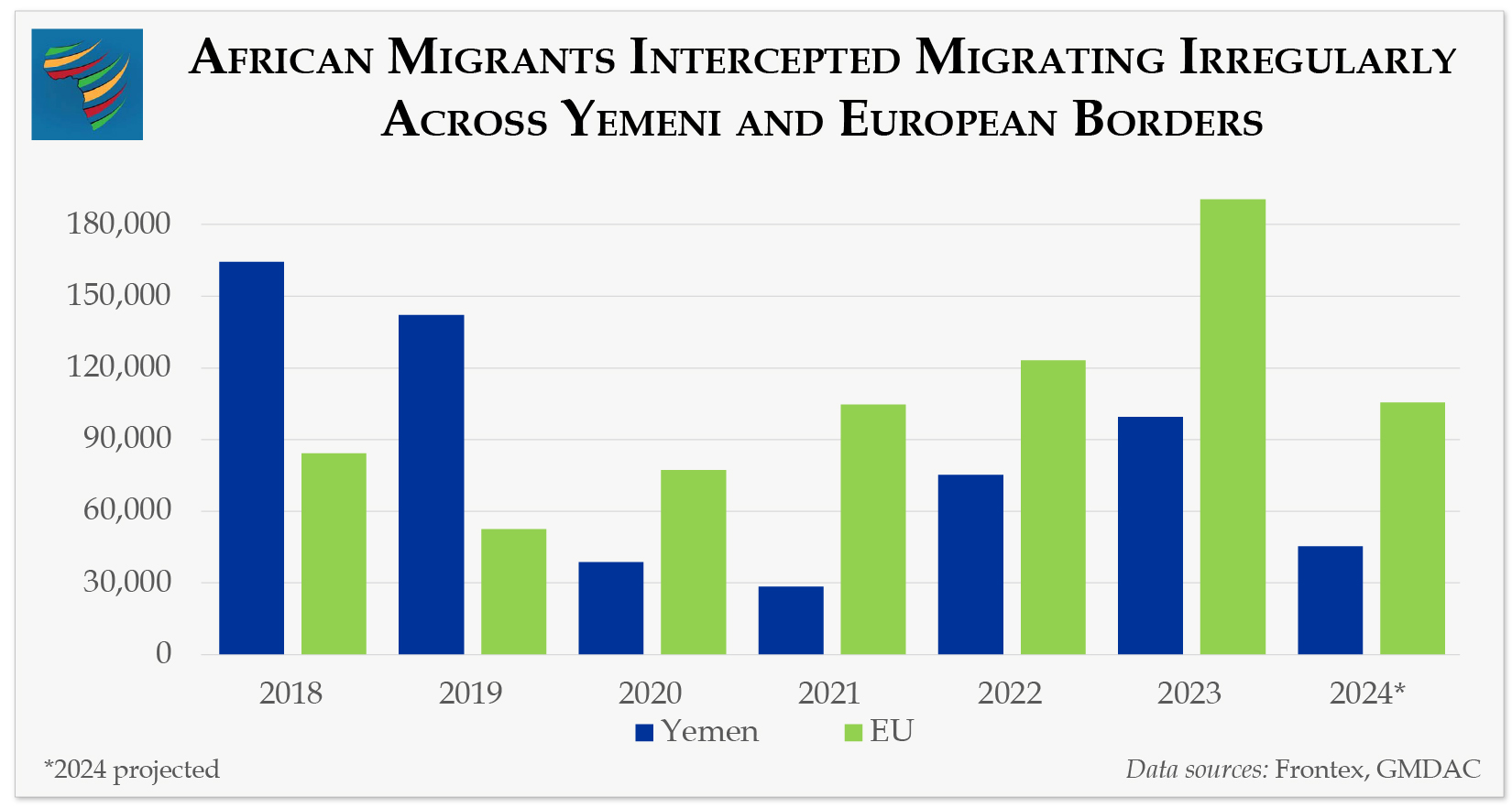

- Heightened restrictions on intercontinental border crossings to Europe and the Arabian Peninsula over the past year have resulted in dramatic drops in African irregular migration off-continent. The 146,000 interceptions of irregularly migrating Africans who reached Europe and Gulf countries in 2024 are roughly half of the 282,000 recorded in 2023.

- The sharp decline in African irregular migration to Europe reflects stepped up European Union-funded interdiction efforts in North Africa (Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt) and West Africa (Senegal and Mauritania). Morocco, illustratively, reports having prevented more than 45,000 crossings to Europe, while arresting 177 migrant trafficking gangs and rescuing more than 10,800 people at sea.

The past year has seen dramatic drops in African irregular migration off-continent.

- The 54-percent decline in irregular migration (to 44,000 people) to Yemen (the primary entry point to the Gulf countries) is a result of a combination of factors including ongoing armed conflict in Yemen and intensified operations by Djiboutian and Yemeni Coast Guards to prevent migrant crossings over the Bab al-Mandeb.

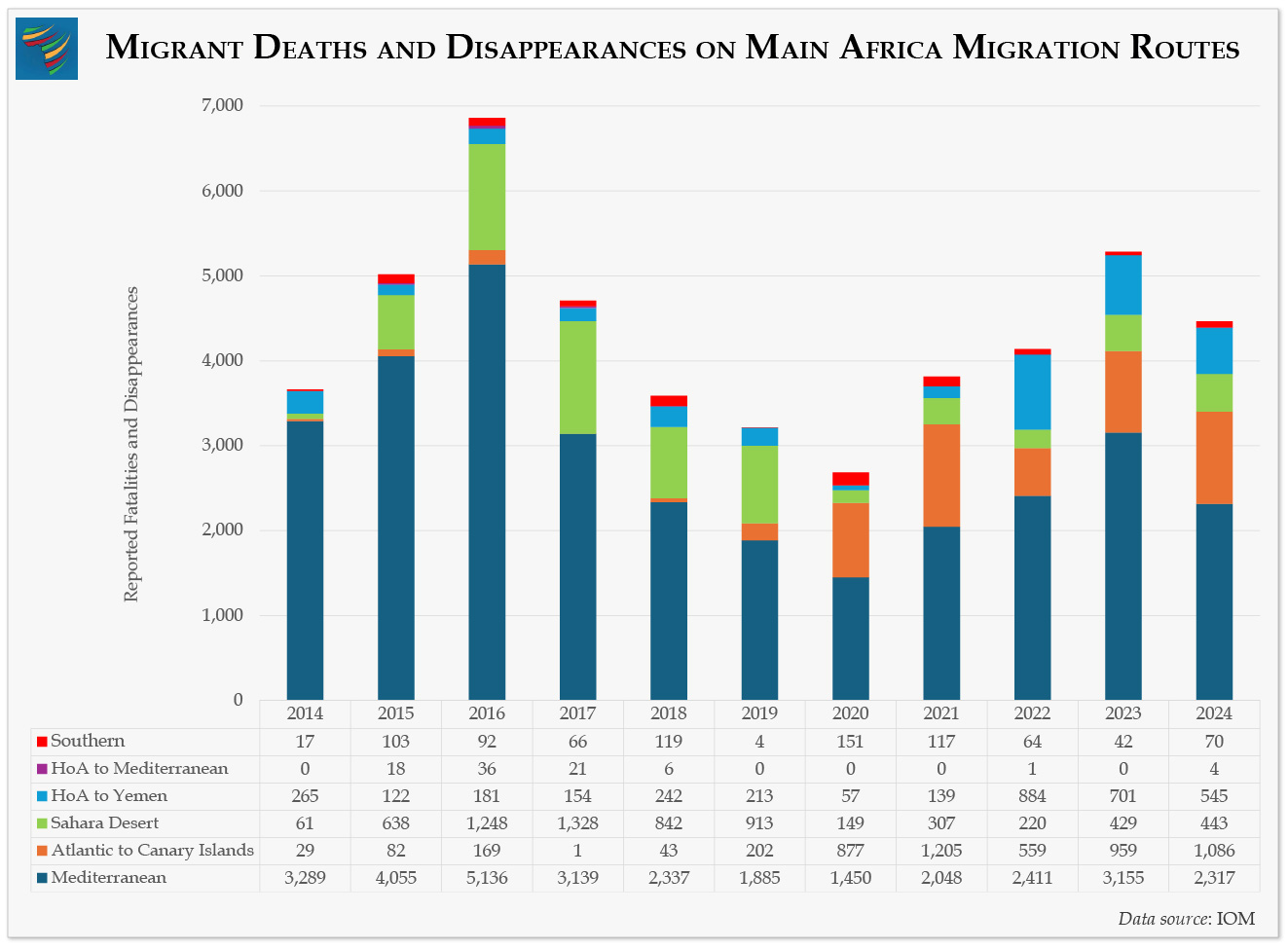

- While recorded migrant deaths and disappearances declined by 15 percent in 2024, there were still an estimated 4,465 migrant fatalities. Three-quarters of these are from attempted maritime crossings to Europe via the Mediterranean and Atlantic.

- Interdictions in North Africa and West Africa have contributed to a 70-percent downturn in European interceptions of African migrants (to 33,500 people) along the Central Mediterranean route, mainly via Libya and Tunisia. The Central Mediterranean route has historically been the most frequented irregular migration pathway for African nationals to Europe.

- With 36,000 African migrants intercepted in 2024, the Atlantic route became the most active irregular passage from Africa to Europe.

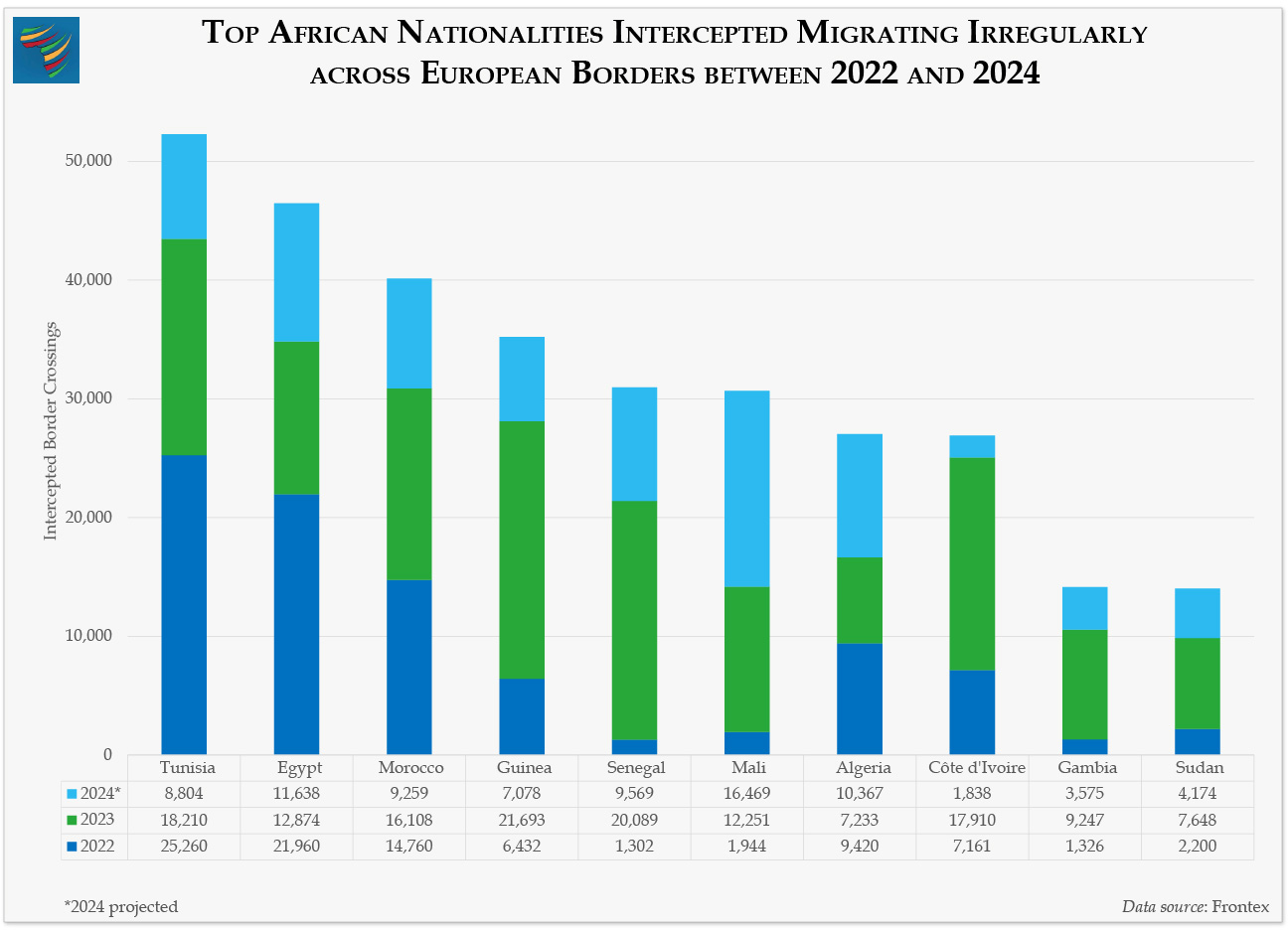

The leading countries of origin for off-continent irregular migration to Europe in 2024 (Mali) and 2023 (Guinea) reflect growing repression and diminished livelihood opportunities under the military juntas.

- Mali was the leading country of origin for irregular migration to Europe in 2024, totaling roughly 16,500 people. In 2023, Guinea topped the list with approximately 21,700 individuals. Both cases reflect the growing repression and diminished livelihood opportunities in these countries under the military juntas who seized power in coups.

- A similar pattern is observed in Tunisia, which leads all African countries in the number of migrants intercepted on European shores over the past 3 years, following the sharp deterioration in political space there.

Increased Informal Migration within Africa

- The United Nations (UN) estimates that Africa saw a 25-percent growth of African migrants (excluding refugees and asylum seekers) living in another African country over the last decade (from 12 million in 2015 to 15 million in 2024). While likely an undercount given its informal nature, nearly all internal Africa migration is labor migration in one form or another. This includes seasonal labor movements as well as permanent resettlements in search of livelihoods, typically in urban economic hubs.

- Given ongoing push factors of unaccountable governance and limited job opportunities in the face of rising youth populations, Afrobarometer surveys indicate almost half of all Africans have considered emigrating—a significant increase compared to the proportion recorded in 2016/2018.

Almost half of all Africans have considered emigrating.

- With Africa’s population predicted to grow by 70 percent by 2050 (to 2.4 billion people), this migratory pressure can be expected to continue—shifting the security, economic, and governance dynamics in each subregion.

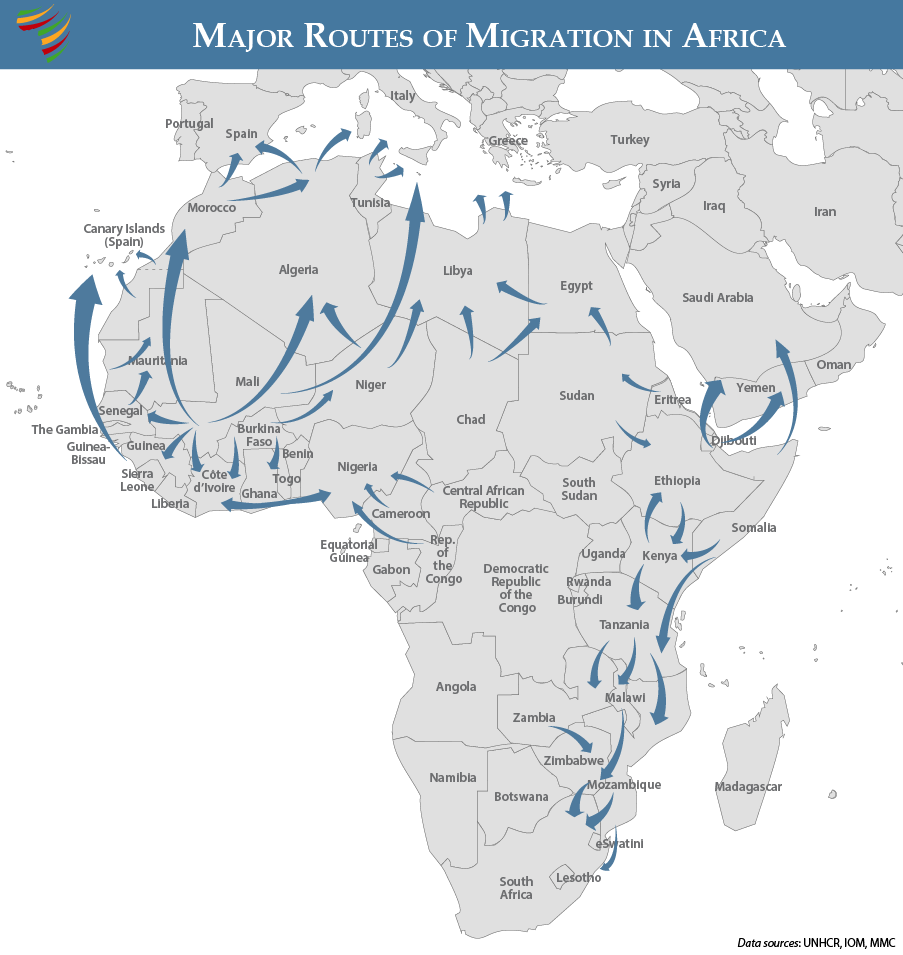

West and Central Africa

- About 70 percent of the migration flows across West and Central Africa involve temporary, seasonal, and permanent migration of workers, with economic hubs such as Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria the key destinations.

- Côte d’Ivoire, illustratively, hosts more than 8 million migrants from Burkina Faso, 402,000 from Mali, and 112,000 from Guinea.

- In addition to heavy-handed governance, the loss of jobs due to a lack of protection of a country’s natural resources is another main driver in this region. It is estimated that illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing is costing countries in the region around 0.26 percent of their gross domestic products (GDPs). This translates into the loss of an estimated 30,000 livelihoods, while pushing another 140,000 people deeper into poverty.

- Central Africa sees limited voluntary intraregional movement between countries, as most economic opportunities are extra-regional to West Africa.

- ECOWAS enjoys freedom of movement for its documented citizens. As a result, an estimated 6 million people have moved within ECOWAS.

- West and Central Africa are home to roughly 500 million people, half of whom are under the age of 15. This includes some of Africa’s fastest growing countries, which will likely further drive the cycle of migratory patterns and place more pressure on urban centers and economic hubs. Mali, the African country with the highest number of migrants intercepted on European shores in 2024, is on track for a 71-percent increase in its population between 2015-2030, expanding from 18 million to 31 million people.

East Africa

- There are at least 3.6 million labor migrants in East Africa, according to UN estimates. Given the instability and drought experience in the region in recent years, the pressure for many more East Africans to migrate intra- and extra-regionally in search of work is growing.

- Despite the East African Community (EAC) economic bloc’s freedom of movement for recognized citizens (as well as the recent steps toward operationalization of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s (IGAD) protocols on the free movement of persons and on transhumance), irregular migration, and the dangers it poses to migrants, remains a problem.

- There are four major migration corridors in the region:

- The Horn of Africa Corridor (toward and within the Horn of Africa)

- The Eastern Corridor (toward countries on the Arabian Peninsula, particularly Saudi Arabia)

- the Southern Corridor (toward South Africa, mostly along the coastal East African countries)

- the Northern Corridor (toward Northern Africa)

- The majority of migratory movements in the Horn of Africa are a result of circular migration, usually for short-term, seasonal work. This migration builds on strong networks between communities of origin (mostly Ethiopian) and their diaspora abroad against a backdrop of land scarcity, unemployment, widespread poverty, and climate shocks.

- The route off continent toward the Arabian Peninsula has historically been one of the world’s busiest maritime migration routes, but it also remains the most challenging for irregular migration, especially in terms of food and water scarcity. Combined, the Horn of Africa and Arabian Peninsula routes comprise roughly 90 percent of East Africa migration.

The majority of migratory movements in the Horn of Africa are a result of circular migration.

- The northern corridor is the least used corridor among East Africans. Sudan has been a leading country of destination of East Africans (mostly Ethiopians) for seasonal work. However, since the conflict in Sudan broke out early in 2023, there has been very little northward migration among East Africans.

- The southern route represents 7-8 percent of East African migration. Of this, 76 percent of the movements have tended to be toward Kenya. Less than a quarter (21 percent) aim to reach South Africa. Transit countries along this corridor, such as Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, regularly detain irregular migrants.

- Most East African migrants on the southern corridor are Ethiopians (85 percent) and Somalis (14 percent). Many of the Ethiopian migrants are male and from areas that have experienced rapid population growth and environmental degradation.

Southern Africa

- Most migration in southern Africa comes from within member countries of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and most head toward the large South African economy. Migrant workers comprise an estimated 9 percent (roughly 1.4 million) of the South African work force.

- South African census data shows that 84 percent of international migrants are from SADC countries. The leading countries of origin are Zimbabwe (48.5 percent), Mozambique (20 percent), Lesotho (11 percent), and Malawi (10 percent).

- A severe El Niño-induced drought impacted much of the region in 2024, causing unemployment, food inflation, and food insecurity to spike. This further heightened temporary employment migration to South Africa.

Innovations to Watch

- Sustained push factors such as repressive governance and population growth coupled with diminished avenues for off-continental migration, underscore the importance of policy innovations on the continent that can best match workers with jobs while strengthening protections for migrants.

- Ghana has become the fifth country committed to offering visa-free access to all Africans, a step toward the African Union’s goal of free movement for all Africans.

Diminished avenues for off-continental migration underscore the importance of policy innovations that can best match workers with jobs.

- An African Development Bank and World Bank plan, dubbed “Mission 300,” aims to light up the homes of 300 million people currently lacking power by 2030. This has the potential to stimulate job creation on the continent while mitigating a key push factor in rural areas.

- In a region where youth comprise three-quarters of the population and where some countries have youth unemployment rates of 50 percent, SADC is encouraging free labor movement among its 16 members, like that of ECOWAS or the EAC.

- Angola, Eswatini, and Malawi have signed onto the 2023 SADC Protocol on Employment and Labour, one of the initiatives aimed at harnessing the region’s demographic dividend by enhancing good labor migration governance practices such as the portability of social security benefits for migrant workers.

- The European Union is expanding work visa opportunities by matching skills and needs between its member states and various countries of origin, including from Africa.

- Germany has charted migration agreements with multiple countries—including Kenya, Morocco, and Nigeria—making more work visas available to skilled workers (from bus drivers to doctors) to help fill Germany’s annual labor shortage of an estimated 288,000 workers due to an aging population. Such arrangements can help increase remittances and provide professional experience that can be shared back home.

- In light of the harsh conditions and threats to personal safety that East African migrants face on the eastern and southern routes, (including trafficking in persons, arbitrary arrests and detention, and xenophobic attacks), IGAD, the UN, and East Africa governments have been cooperating to improve access to essential services along these routes.

- The Philippines’ Department of Migrant Workers was established to consolidate government-wide efforts to protect the rights and welfare of overseas Filipino workers. This experience may hold lessons for safeguarding African citizens working abroad, especially for African countries who appear to be relying on overseas workers as part of their economic development strategy.

Additional Resources

- Chris Horwood and Bram Frouws, eds., “Mixed Migration Review 2024,” Mixed Migration Centre, 2024.

- International Organization for Migration, Mixed Migration Centre, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “On This Journey, No One Cares if You Live or Die: Abuse, Protection and Justice along Routes between East and West Africa and Africa’s Mediterranean Coast,” Vol. 2, 2024.

- Wendy Williams, “African Migration Trends to Watch in 2024,” Infographic, January 9, 2024.

- Wendy Williams, “Shifting Borders: Africa’s Displacement Crisis and Its Security Implications,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 8, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, October 2019.

More on: Migration and Forced Displacement