Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português | العربية

Unregulated logging of the Congo Basin rainforests threatens to undercut the livelihoods of millions of households in the region, empower transnational organized criminal networks, and disrupt water cycles in West Africa and the Nile River Basin.

A logging storage area near Dolisie, Republic of the Congo. (Photo: jbdodane)

Highlights

- The rapid degradation of the Congo Basin rainforests poses a threat to the livelihoods of millions who rely on the forests’ resources and the regulating role the forests play for African rain patterns and carbon sequestration.

- Weak forest management is empowering transnational organized criminal networks and armed militant groups who are playing an increasingly central role in resource extraction from the Congo Basin.

- Illicit logging, mining, and wildlife trade in the Congo Basin is enabled by the complicity of senior public officials who profit from their positions overseeing the management of these national resources.

- Better management and protection of the Congo Basin rainforests will require enhanced forest domain awareness as well as realigning the incentives for local communities, public officials, and international logging interests.

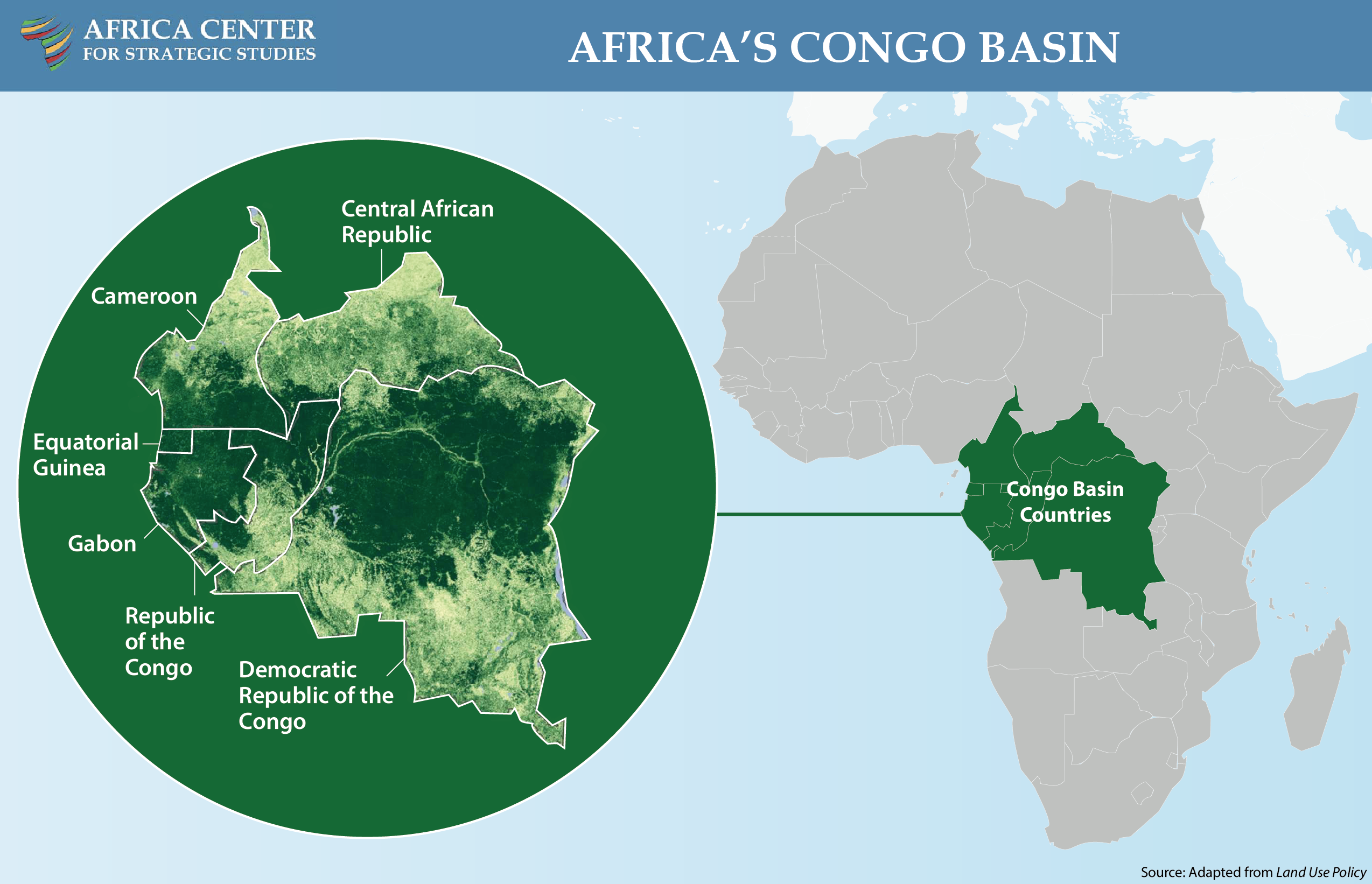

Known as the planet’s “second lung,” the Congo Basin is one of Earth’s most vital forested regions. Comprising almost 200 million hectares of dense rainforest and peat swamp soils, the Congo Basin absorbs more carbon dioxide than any other region in the world. Its annual net carbon dioxide absorption is six times that of the Amazon rainforest.1 The Congo Basin is an invaluable treasure not just for the six countries that host the bulk of the forest—Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo—but for Africa and the world. Without an intact Congo Basin, efforts to mitigate global warming and its many extreme side effects will fall short.

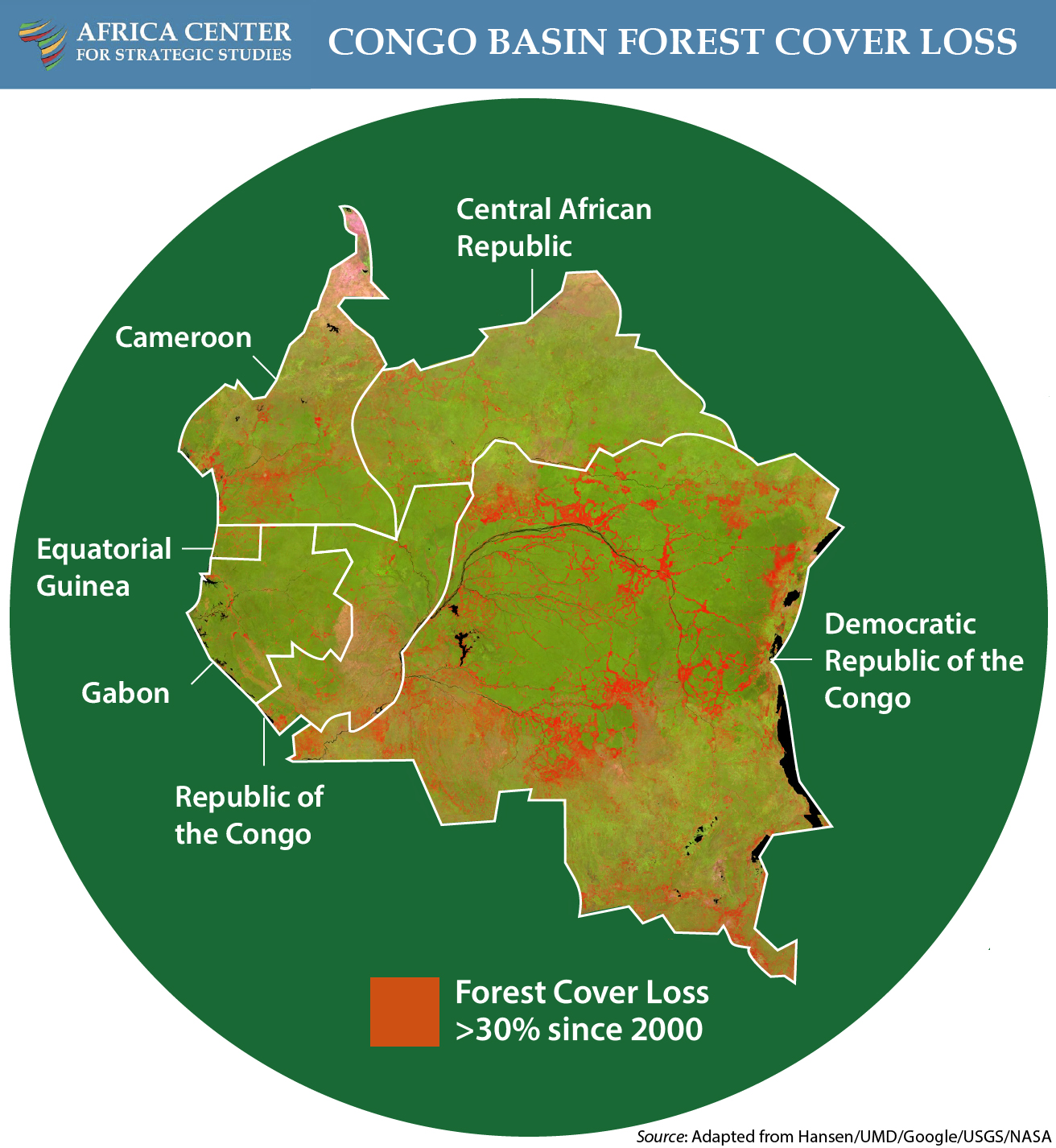

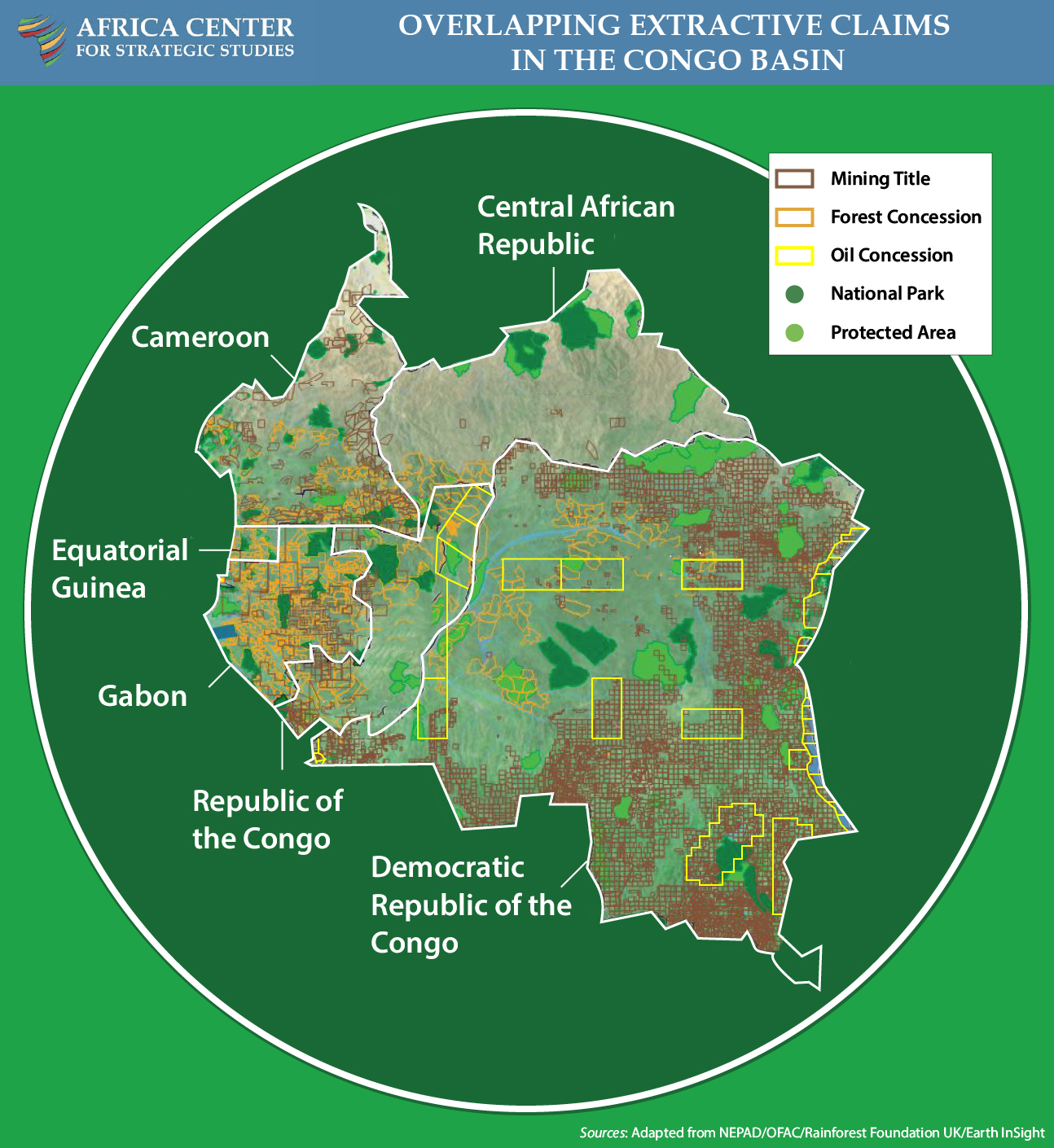

Yet, estimates are that the Congo Basin forests are shrinking by 1 to 5 percent a year and that 30 percent of forest cover has been lost since 2000, largely due to unregulated commercial logging and mining.2 The annual degradation in the DRC’s rainforest alone results in carbon emissions equivalent to 50 coal-fired power plants operating for a full year.3 These figures may be significant underestimates as satellite imagery and on-the-ground monitoring are currently insufficient to establish a reliable baseline. What is known is that 50 million hectares (or a quarter of the Congo Basin rainforests) are already under logging concessions. Estimates are that illegal logging and associated trade (ILAT) from the plundering of the region’s valuable forest resources is costing the continent $17 billion annually.4

Without an intact Congo Basin, efforts to mitigate global warming and its many extreme side effects will fall short.

The Congo Basin’s rare and high-value hardwood species are particularly in global demand. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reports that Africa’s share of rosewood exports to China rose from 40 percent in 2008 to 90 percent in 2018. China is the world’s largest importer of illegally logged wood.5

The forestry sector in the DRC accounts for 9 percent of its GDP and an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people in the country rely on the forests for their livelihoods. Up to 55 million people in the region derive economic benefits from the forests. Due to corruption, however, local communities often only see a fraction of the financial benefits from this extraction.

Illegal logging also threatens the 30 billion metric tons of carbon stored by the Congo Basin—the equivalent of 3 years of global fossil fuel emissions.6 The annual carbon sequestration value of the Congo Basin rainforests is estimated to be $55 billion, or more than a third of the region’s GDP.7 With approximately 10,000 species of tropical plants—30 percent of which are unique to the region—the region also holds extraordinary importance for global biodiversity.

Pressure on the Congo Basin forests is further exacerbated by illegal wildlife trade (IWT) and illegal mining, including the high concentrations of cobalt and coltan.

Given the high-value revenue streams, weak forest management, and lax government oversight of these sectors, transnational organized criminal networks and armed militant groups are playing an increasingly central role in resource extraction from the Congo Basin. This poses both a growing security and economic threat to the region.

Threats to this ecologically unique region, in turn, will negatively impact the regulation of the continent’s water cycle and the planet’s atmosphere, making the Congo Basin an epicenter of regional and global stabilization efforts.

A Vital Resource

The region and its peat swamp forests absorb 370 million metric tons of carbon emissions per year, making it the world’s most important terrestrial carbon sink.

The Congo Basin rainforests represent roughly 70 percent of Africa’s forest cover.8 The region and its peat swamp forests absorb 370 million metric tons of carbon emissions per year, making it the world’s most important terrestrial carbon sink. Peatland ecosystems are among some of the most efficient and critical for combatting climate change.

The few studies that have been conducted in the Congo Basin indicate that the region strongly regulates regional precipitation patterns.9 This includes being the source of 17 percent of the moisture for West Africa (including the Sahel) and 30-40 percent of the annual rainfall in the Ethiopian highlands.10 The depletion of these forests poses a risk to this “water pump” service that the Congo Basin provides the continent. In practical terms, the survivability of the Nile River depends on the health of the Congo Basin rainforests. Studies of the more widely researched Amazon rainforest warn of a “savanization” as a result of the loss of forest cover and its water retention capabilities.

The Congo Basin is one of the world’s largest unexplored forest ecosystems with a rich diversity of over 400 mammal species (including forest elephants, rhinoceri, hippopotami, giraffes, bonobos, and gorillas), 1,000 bird species, and 700 species of fish.11 The forests within the Basin act as a natural filtration system for the water coursing through the Congo River, making it safe for human consumption.12 Many of the plant species in the region have been used for medicinal purposes and are under study for broader applications to treat various types of cancer and inflammatory diseases.13

With the growing recognition of the importance of the Congo Basin, governments in the region have granted protected status to approximately 22.6 million hectares of rainforest in Central Africa, equivalent to 14 percent of its surface area.14 While an important start, much more will need to be done to safeguard the region’s unique natural and economic benefits.

Need for a Stronger Baseline of Knowledge and Monitoring

A scientist checks a flux tower monitor measuring the carbon dioxide in trees in the Yangambi Biosphere Reserve, DRC. (Photo: AFP/Guerchom Ndebo)

Better information is essential for any effective forest management and ecosystem conservation policy to protect the Congo Basin rainforest. More research is needed to better document the extent of tree cover and forest degradation, and to more precisely quantify the contribution of these woodlands to global carbon flows and their role in other climate challenges.

Progress on this front is being realized. A new generation of satellite technology is proving to be a valuable data source for large-scale monitoring of tropical forests that are often difficult to access.15 Inventory data from numerous forest concessions have recently been used to provide a summary of their functional diversity. Moreover, the inauguration of the first flux tower (to measure the exchange of greenhouse gases) in the Congo Basin in 2020 augurs well for a better understanding of the forests’ carbon flux. The availability of satellite imagery for the region, however, continues to be limited.

The need for field observations, moreover, limits the mapping of the spatial distribution of forest carbon stocks at the basin scale. Monitoring forest resources requires regularly gathering information on forest attribution, harvesting, transportation, processing, and trade of these resources or their products. Because field observations are costly, only inventory data from forest concessions (owned by private firms) are available, giving just a part of the real potential of Congo Basin forests and biomass.

Monitoring forest resources requires regularly gathering information on forest attribution, harvesting, transportation, processing, and trade of these resources or their products.

With the support of international organizations, including the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) framework has elevated forest monitoring systems in Congo Basin countries. This includes measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) functions to produce high-quality, reliable data on forests and forest-carbon estimates.

Although the above processes have strengthened the empirical baseline in Congo Basin countries, further capacity-building is needed in the collection and integration of available data to trigger real-time intervention decisions.

Protecting Community Rights and Livelihoods

In the Central African context, all lands belong to the state. Forest management policies are designed and implemented by governments in close collaboration with multiple actors. National governments generate revenues from logging via taxes at various points in the supply chain from the attribution of the forest concessions to the logging operations and timber trade.

Rights to use the forest resources are primarily based on the following considerations:16

- Leasing/concessions. Some countries own all the land but lease it via concessions.

- Land tenure. In many countries, local communities may have some land use rights, but recognition of the full scope of rights is absent. This can cause confusion and competing claims on the same land by different actors.

In the Congo Basin countries, indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLC) are only granted customary rights. Customary rights allow the IPLCs to manage lands acquired by their ancestors. This type of land is controlled by the chief, who works on behalf of the communities. Customary rights include the right of pre-emption: the right to be consulted first before any decision from the state to transfer the land to a third party is given.

Inequitable redistribution of revenues is a point of tension with local communities—made more acute by expanding forestry, mining, and agro-industry interests.

These arrangements leave IPLCs in a disadvantaged position, however, since the allocation of tax revenues from logging operations aligns with the statutory rights on land and area controlled by the state. The inequitable redistribution of these revenues by governments is often a point of tension with local communities. These tensions are growing more acute as expanding forestry, mining, and agro-industry interests are leading to increased land use conflicts. At times, this results in violent incidents between local communities and commercial logging interests.17

This process poses additional problems for indigenous populations whose notion of development is quite different from that of the legal application of land tenure law. Indeed, the type of development described generally in the law is practically inapplicable for indigenous peoples because they don’t build long-lasting structures and are nomadic, moving from one place to another.

A system for redistributing the income generated by the management of forest resources, particularly timber, will only be successful and sustainable if it includes recognition of the right of first ownership by IPLCs and a transparent delineation and enforcement of the quotas for the various beneficiaries. Failure to do so risks a boomerang effect, with the aggrieved parties becoming forest resource spoilers as they seek a means of survival.

The emergence of the REDD+ process has given much greater prominence to the issue of more equitable benefit sharing in recent years. However, competing uses of the forest resources will require intersectoral land use planning. Establishing national land use plans in the Congo Basin countries would enable coordination of the different sectors to avoid conflicts of use and instead protect local populations’ livelihoods.

Illegal Logging, Wildlife Trafficking, and Mining

Despite considerable efforts to improve the enforcement of forestry laws, governance, and trade in the Congo Basin countries, illegality still occurs throughout the timber supply chain. Some reports have asserted that 90 percent of the timber from the Congo Basin rainforests may be illegally sourced and facilitated by high-level crime.18 This is due to a combination of factors including lack of staff capacity, poor coordination with other enforcement agencies (e.g., customs), and insufficient information about the main areas of illegality in the supply chain.19

This underscores the importance of forest management systems to systematically track timber and timber byproducts. The law in all Congo Basin countries provides guidelines on traceability along the entire supply chain—from the forest to export—for industrial and artisanal logging.20 Governments implement timber legality assurance systems (TLAS), revenue collection, traceability, and other functions through comprehensive timber and forest information management systems. These information management and traceability systems are all mandatory but are deployed at varying levels of sophistication across each country.

A convoy of trucks carrying logs to the port of Pointe-Noire in the Republic of the Congo. (Photo: Boussou Gaston)

In Cameroon, the government developed the first computerized forest information management system (SIGIF) in 1998 to facilitate the management of forest exploitation permits. However, it must still include the parallel and paper-based timber traceability system. Since 2020, the government has been deploying a mandatory traceability system embedded in a second-generation SIGIF (SIGIF 2).

The Gabonese government created the Forestry and Timber Industry Execution Agency (AEAFFB) in 2011 to better implement activities in the timber sector and on forest product traceability. Some nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and private sector actors have developed a voluntary digitally based timber traceability system that collects and publishes data, is mobile-enabled, and runs on the internet. The government, however, has not officially recognized these systems pending further review.

Unmarked logs in the DRC likely indicate illegal logging. (Photo: TRAFFIC/Denis Mahonghol)

In the DRC, the government has initiated numerous computerized timber traceability systems since they began negotiations with the European Union (EU) on the comprehensive Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade Voluntary Partnership Agreement (FLEGT VPA) in 2010. Between 2013 and 2015, this culminated in the development of a state-owned SIGIF and a timber traceability and legality management platform (TRABOIS). Although these systems are mandatory, they are not operational.

In Equatorial Guinea, the government has adopted timber tracking as one of the strategic mechanisms to ensure that national forestry resources are rationally exploited to provide sustainable tax revenues and socioeconomic development opportunities while preventing the degradation of resources.

In the Republic of the Congo, following the signing of the FLEGT VPA with the EU in 2010, the government has been developing a computerized legality verification system (SIVL) to combat illegal logging, which has been identified as one of the critical problems impacting its forestry sector. Although the needed modules are developed and embedded in the Ministry of Finance and Budget data center, the system is not yet operational.

In CAR, the government has conceived of a dedicated TLAS. This includes traceability components for tracking timber along the supply chain—from harvest to export—as well as compliance and computerization tools for real-time access and control. Still, this system has yet to be developed and deployed.

Many Congo Basin countries continue to lack operational traceability systems that prevent them from effectively controlling and monitoring the timber trade.

Several additional Congo Basin countries have initiated forest observation systems to support transparency as part of the FLEGT VPAs signed with the EU to curtail the flow of illicit and unsustainable timber trade to Europe.

Despite these agreements and modules, many Congo Basin countries continue to lack operational traceability systems, thereby preventing them from effectively controlling and monitoring the timber trade from harvest to final consumption within the country or for export. Key obstacles include the acquisition and installation of needed equipment, training of actors and stakeholders, and overcoming hesitancy and resistance from timber operators over additional costs without perceived improved efficiencies.

The timber tracking system developed by the Tanzania Forest Services Agency provides a practical, cost-effective, and scalable model that can be replicated in the Congo Basin region. The system is easily accessible via mobile devices programmed with pre-customized selection options, reducing human error. This ensures chain of custody tracking by enabling monitors’ access to inspection reports from other checkpoints. It also allows real-time data access at the headquarters to enhance control, encourage diligence, and maintain a quality database.

Law Enforcement Coordination and Information Sharing

It is often said that whoever has the information has the power. In the context of ILAT in the Congo Basin, organized criminals are typically one step ahead of politicians and law enforcement officers when it comes to information. To combat ILAT, information gathering, management, and use is critical. Criminals have developed effective information systems drawing from a network of informants on the ground working cooperatively and exploiting leakages in the regulatory frameworks.

Defeating established criminal networks requires consistent and quality coordination and information exchanges between those entrusted to enforce the law within a country as well as between counterparts across borders to address security issues between countries. In practical terms, such interdepartmental and intergovernmental coordination to share knowledge and solve problems often comes down to strong relationships rather than just formal mechanisms.

TWIX Systems: Connecting National Enforcement Agencies Across Europe and Africa

Approximately 3,000 enforcement and management officials in Europe and Africa are currently connected on the Trade in Wildlife Information eXchange (TWIX) platform.

Led by the Central African Forest Commission (COMIFAC), AFRICA-TWIX was established in 2016. Combined with the European Union-TWIX (2005), the Southern African Development Community-TWIX (2019), and the Eastern Africa-TWIX (2020), the TWIX network provides online tools developed to facilitate information exchange and international cooperation between law enforcement agencies in the fight against illegal wildlife trade across Europe and Africa.

Law enforcement’s ongoing challenge is ensuring smooth and timely communication between countries when dealing with transnational wildlife smuggling networks. Available to enforcement and management officials responsible for the implementation of regulations concerning international wildlife trade by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the TWIX platform helps connect officials across borders, allowing them to share information and expertise rapidly.

Interest in the tool has led to an ongoing deployment in West Africa and a request from Asia.

Facilitating regular communication between international enforcement agencies has proven highly effective in helping to disrupt transnational smuggling networks—an effort that will need to be sustained by all participating countries if the full impacts are to be realized.

To coordinate efforts and information between its member countries, COMIFAC has set up multiple working groups to address pressing issues affecting the subregion. This includes working groups on the Convention to Combat Desertification (GTCCD), Climate Change (GTCC), Biodiversity in Central Africa (GTBAC), Protected Areas and Wildlife (SGTAPFS), and Forest Governance (GTGF). It is within the latter that all discussions related to forest governance, ILAT, and other related issues fall. The format of the meetings is face-to-face and within a quarterly or semestral period, with the aim of building trusted relationships.

The AFRICA-TWIX platform, like the other TWIX systems, links law enforcement officers to one another (via mailing lists) and to restricted databases that include wildlife identification tools, legal texts from the platform’s member countries, training materials, and a database of wildlife seizures, among other resources.

In the Congo Basin, organized criminals are typically one step ahead of politicians and law enforcement officers when it comes to information.

Launched in 2016, this platform has played a crucial role in coordinating action on the ground, linking nine countries: Burundi, Cameroon, CAR, Chad, DRC, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda. More than 500 affiliated law enforcement officers are on this platform, including personnel from specialized organizations like the World Customs Organization (WCO), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL).

The collaborative work of these officials, recruited from both headquarters and the field, has triggered 13 international investigations into wildlife crimes. Coordination of efforts and information exchange in real time is the start of a solution to the fight against ILAT.

A Fight Against Corruption

Countries with abundant natural resources often face endemic corruption and weak accountability. This is because natural resources provide a ready revenue stream to which government officials can control access—benefiting themselves and their commercial partners. These officials, in turn, have little incentive to strengthen oversight and enforcement mechanisms allowing the natural resource exploitation, self-enrichment, and political impunity cycle to grow progressively more powerful.

Investigations in the Republic of the Congo have revealed that timber companies routinely bribe ministers and other senior officials to illegally obtain timber concessions, avoid penalties for overharvesting, and export in excess of quotas.21 In the DRC, similarly, the government revealed that many logging concessions had been allocated through influence peddling in breach of the country’s laws.22 Among the leading offenders was the logging company Congo King Baisheng Forestry Development owned by China-based Wan Peng International.

Opaque corporate structures and secrecy jurisdictions including in Hong Kong and Dubai also facilitate deforestation in the region by allowing companies to obscure their beneficial owners and to avoid taxes and regulation.23

This illicit political economy surrounding forestry exploitation in the Congo Basin is well entrenched. In Cameroon, for example, the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife is ranked among the 10 most corrupt out of 150 government agencies. Cameroon, in turn, rates better on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index than nearly every other country in the Congo Basin region. The region as a whole has a median ranking of 157 (out of 180 countries). The region’s corruption crisis, therefore, is at the heart of the illegal exploitation of the Congo Basin’s forests.

Officials have little incentive to strengthen oversight and enforcement mechanisms allowing the natural resource exploitation, self-enrichment, and political impunity cycle to grow progressively more powerful.

Local communities and indigenous groups are particularly vulnerable to corruption in the Congo Basin forests. From officials accepting kickbacks to private and public sector collusion on opaque resource extraction contracts, corruption provokes environmental degradation and destroys local livelihoods. Making concrete gains on environmental protection will depend on greater transparency and independent oversight.

Illicit logging is also deadly for environmental defenders worldwide.24 Environmental journalists are frequently harassed, assaulted, and killed, making it the most dangerous field of journalism after war reporting. This underscores that criminal networks are often behind rainforest exploitation. Surveys show 70 percent of environmental journalists have been attacked for their work.25 Yet, it is only by investigating and exposing environmental violations (and the collusion by public officials that often goes along with it) that citizens can be informed of these illegal activities and how public resources are being misdirected. Achieving global climate and biodiversity objectives will require tackling the hydra of corruption.26

In most countries, national anticorruption units exist but are rarely enforced. At times, investigators can track corruption activities involving illegal logging on the ground, report on them, and transmit them to the public prosecutor for criminal prosecution. Yet, few cases lead to convictions due to the political influence of officials colluding with the illicit logging activities.

The Dja National Park in Cameroon. (Photo: TRAFFIC/Andrew Walmsley)

Forestry ministries in Congo Basin countries are working increasingly with foreign trade associations such as the China Wood and Timber Product Distribution Association (CTWPDA) to uphold standards to enhance the transparency and the legality of their extraction of logging resources from Central Africa. Such agreements will also subject foreign firms to sanctions for violations.

Although most Congo Basin countries have now established the legal frameworks to counter corruption, more work is needed to ensure the enforcement of these frameworks. This will require enacting severe penalties for corruption around illegal logging, thereby diminishing the impunity currently enjoyed by senior officials who are complicit.

Priority Actions Needed

The timber trade in the Congo Basin is an essential source of income, integral to national economies, and provides a livelihood to local communities. Ensuring the sustainable production and consumption of timber in the Congo Basin is a vital feature for any path to reform. Yet a surging demand for tropical wood (primarily from Asia but also from Europe and America) exacerbated by corruption, resource mismanagement, and ineffective regulation, makes it too easy for criminals to harvest and trade in threatened timber illegally.

The many gaps in the current protection of the Congo Basin forest resources underline that only a holistic and multitiered approach can address the unregulated and unsustainable exploitation of the Congo Basin’s invaluable natural assets.

At the National Level

Improve forest domain awareness. A prerequisite for protecting and managing the valuable forests and peatlands of the Congo Basin is to establish reliable baselines of forest inventories across the region. The Central African Forest Observatory, the scientific arm of COMIFAC, has taken the lead in this process. It will need to be supported with additional satellite imaging (building on efforts by the United States and the World Resources Institute) as well as with training networks of forest rangers and NGOs who can conduct field-level assessments to generate reliable forest inventories for each country in the region.

Develop comprehensive land use plans. While detailed knowledge of the forest resources in the region is an essential baseline, a comprehensive land use plan is needed to navigate the many competing interests of these lands sustainably for the long-term protection of the Congo Basin forests. This must be supported by robust national legal frameworks and the reliable implementation of the national land use planning policies sector by sector to avoid land disputes.

Establishing national land use plans in the Congo Basin countries would enable coordination of the different sectors to avoid conflicts of use and instead protect local populations’ livelihoods.

Enable and operationalize traceability systems. Verifying timber legality and tracking revenue from legitimate forest sources are critical tools for enforcement agencies to protect forest resources. While traceability and legal verification systems are in place in some countries in the Congo Basin, operationalizing these systems throughout the entire region—potentially drawing on the Tanzania model—is still needed to avoid criminal entities exploiting these gaps.

Incorporate forest protection into national security strategies. Forest resources are among the most valuable and sustainable national assets of the Congo Basin countries. Safeguarding these assets must be more centrally incorporated into the national security strategies of each country. Elevating the importance of this nontraditional security threat into the planning and structures of security agencies will facilitate the realignment and redeployment of security and intelligence resources to counter the illegal exploitation of the forests to the detriment of citizens.

The illicit political economy surrounding forestry exploitation in the Congo Basin is well entrenched.

Build national capacity on combatting financial crimes. ILAT thrives in the Congo Basin because of the sweeping authorities controlled by senior government officials responsible for managing these forest resources. This, in turn, creates financial incentives for these officials to act against the public’s best interests. To reduce this vulnerability, the regulatory chain of authority must be expanded beyond a single minister or official and entail a multilayered authorization process overseen by an independent oversight board comprising civil society actors.

Given the impunity many senior officials enjoy for their collusion in ILAT and IWT, Congo Basin governments may also consider establishing special politically insulated corruption courts as part of their judicial capacity-building efforts to combat financial crimes. Such courts as well as other components of the legal system (from law enforcement officers to prosecutors) can be supported by regional bodies such as the Action Group against Money Laundering in Central Africa (GABAC) and global networks such as INTERPOL and UNODC.

At the Local Level

Develop equitable benefit-sharing formulas for local communities. As they live closest to the forests, local communities are the first link in the chain of forest protection and the cornerstone of any successful policy to combat illegal logging.

Local communities are also the most insecure stakeholders in the forest management system. Lacking information and the skills to defend their interests in the legal arena, local communities risk being duped out of access to their customary rights to the land by logging corporations or colluding with public officials. Payments received for foregoing such access do not compensate for the permanent loss of livelihoods, ancestral lands, and cultural traditions for these communities. These are the significant human and economic costs that accompany unsustainable logging of the Congo Basin.

To counter this exploitation of local communities, customary rights provisions must figure centrally in national land use planning processes. This should be accompanied by proactive educational outreach to local communities about their rights and alternative sustainable management models that maintain livelihoods and revenues from preserving the forests. National and international NGOs can contribute to this process by ensuring local communities have a better understanding of the resources and revenue flows provided by the forests.

Protecting the livelihoods of local communities will also require ensuring sustainable revenue flows to these communities so they have financial incentives to cooperate in the protection of these forests. In addition to incorporating local communities into any international conservation investment schemes (see below), prohibiting concessions for any commercial logging on designated “community forests,” such as the 5,000-hectare tracts of forest allocated to communities in Cameroon and other countries in the Congo Basin, would reduce local forest communities’ perpetual vulnerability to exploitation.

At the Regional Level

Establish a coordinated financial information-sharing mechanism in transboundary areas. Criminals often exploit weaknesses in the financial arena, such as cash in hand or other mechanisms related to the local transfer of large amounts of money. This can also hide money laundering activities. Establishing a shared platform among the region’s ministries of forestry, finance, and customs under the leadership of national financial investigation units can better track revenues associated with the cross-border timber trade to ensure this reconciles with the logging activity that has been recorded.

Expand AFRICA-TWIX. AFRICA-TWIX has been an effective mechanism for combatting ILAT and IWT. A priority for COMIFAC is to ensure all Congo Basin countries are fully operational on the AFRICA-TWIX platform. The key limitation to this is funding. This will require training and funding support from donors.

(Photo: Marco Vech)

The planned creation of an ASIA-TWIX in addition to the existing EU-TWIX will greatly facilitate interregional information sharing on illegal logging and wildlife trafficking by law enforcement. Increasing the number of criminal investigations and prosecutions for ILAT and IWC in the Congo Basin will hike the costs to illegal logging operations and create a tangible deterrent effect.

Operationalize a subregional strategy to combat transnational organized crime and illicit financial flows. To better harmonize the efforts of individual countries when dealing with a transnational threat, the Congo Basin governments must operationalize a subregional strategy to combat transnational crime and illicit financial flows. This strategy can be led by the secretariat of the Central African Police Chiefs Council (CCPAC) in consultation with the expertise to be found at the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) Commission, the Bank of Central African States (BEAC), the Banking Commission of Central Africa (COBAC), and GABAC.

Strengthen regional security cooperation around ILAT and IWT. The Congo Basin forests face security threats not only from illegal logging and mining operations but also from nonstate armed groups and violent extremist organizations who are tapping the revenue streams from these forests—both accelerating their degradation and further enabling the coercive capacity of these malefactors. Combatting these security threats will require enhanced regional security cooperation around illegal logging, mining, and wildlife operations.

The Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) Security Council facilitates transboundary security cooperation, including around the Tri-National Dja-Odzala-Minkébé (TRIDOM) complex involving 11 national parks. Spurred by an attack in the Bouba Ndjida National Park in Cameroon that saw the slaughter of 400 elephants (and theft of their ivory) in 2012 by Sudanese poachers who passed through Chad and Nigeria,27 this cooperation typically entails supporting “ecoguards” and the right of pursuit between countries. However, security force deployments along the borders and in the parks are episodic, enabling illicit traffickers to exploit the porous border areas.

As nonstate armed groups grow more sophisticated, harmonizing the efforts and expanding the capacity of the Congo Basin security actors to capably protect their shared national interests is increasingly essential. This includes facilitating greater judicial sector harmonization. Currently, if a Gabonese illicit logger is captured in the Republic of the Congo, he will face a lighter sentence than he would back home. As ECCAS and its international partners look to enhance and institutionalize regional security, they may draw lessons from ECCAS’s successful Yaoundé Code of Conduct that established a regional maritime security architecture to combat piracy in 2013.

At the International Level

Expand and regularize satellite imaging of the region. Given its expansiveness and limited government resources, effective monitoring and management of the Congo Basin rainforest will require expanded and consistent satellite imaging surveillance to assess changes in forest cover and health. The Gabonese Agency for Space Studies and Observations (AGEOS) generates regular satellite imagery of its forests, which enables decision-makers to orient their policies on a scientific and practical basis. The reliability of this satellite imagery has, in turn, become the basis for global carbon capture schemes that are slated to earn Gabon $150 million. The adoption of regular satellite imaging of the forests in other Congo Basin countries can generate real-time observation and evaluation of biomass stock of their forests.

Support international finance schemes to incentivize protection of vital international assets. At the Dubai Climate Summit in 2023, Brazil proposed the adoption of a Tropical Forests Forever Facility that would pay countries for protecting their tropical rainforests.28 The investment facility aims to create an interest-bearing fund that can reliably compensate and financially incentivize countries to conserve these global assets. The hundreds of millions of dollars the fund would be expected to generate year after year for the Congo Basin countries would provide a sustainable revenue stream that would support conservation efforts and surpass the proceeds that would be generated from one-time logging concessions.

Strengthen security cooperation around ILAT and IWT. To curb the international dimensions of ILAT and IWT will require the cooperation and support of international partners. Working bilaterally and in support of TWIX, international actors can commit their expertise in combatting illicit financial flows to help surveil and interdict ill-gotten revenues from illegal logging and wildlife trafficking in the Congo Basin. International actors can also heighten the financial costs of ILAT by sanctioning and freezing the bank accounts of known traffickers. International security partners can furthermore support regional security cooperation efforts by sharing their expertise in combatting ILAT and helping Congo Basin security actors harmonize their efforts around an integrated regional strategy.

Denis Mahonghol has 24 years’ experience in forest governance and conservation in Central Africa. His main areas of work include forestry research, trade, timber traceability and legality, forestry and wildlife law enforcement, capacity-building for public institutions in decision-making and wildlife trade monitoring (flora and fauna). Currently, Mr. Mahonghol is the Director of TRAFFIC International’s Central Africa Program Office.

Notes

- ⇑ Cheick Fantamady Kanté, “Preserving the Forest of the Congo Basin: A Game Changer for Africa and the World,” Africa Can End Poverty (Blog), World Bank, July 04, 2024.

- ⇑ Marion Ferrat, Sanggeet Mithra Manirajah, Freddy Bilombo, Anna Rynearson, and Paul Dingkuhn, “Regional Assessment 2022: Tracking Progress Towards Forest Goals in the Congo Basin,” Climate Focus, November 2022.

- ⇑ Global Witness, “Total Systems Failure: Expositing the Global Secrecy Destroying Forests in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Report, June 26, 2018.

- ⇑ Bob Koigi, “Illegal Chinese Timber Business is Devastating Africa’s Forests,” Fair Planet, September 5, 2018.

- ⇑ Sam Lawson, “Illegal Logging in the Republic of the Congo,” EERP Paper 02, Chatham House, April 2014.

- ⇑ Oluwole Ojewale, “Balancing Protection and Profit in the Congo Basin,” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, March 14, 2023.

- ⇑ Ian Mitchell and Samuel Pleeck, “How Much Should the World Pay for the Congo Forest’s Carbon Removal?” Center for Global Development, November 02, 2022.

- ⇑ The Program on Forests (PROFOR), “Understanding the Forest-Water Interactions in the Congo Basin,” June 16, 2024.

- ⇑ Thomas Sibret, Marijn Bauters, Emmanuel Bulonza, Lodewijk Lefevre, Paolo Omar Cerutti, Michel Lokonda, José Mbifo, Baudouin Michel, Hans Verbeeck, and Pascal Boeckx, “CongoFlux – The First Eddy Covariance Flux Tower in the Congo Basin,” Frontiers in Soil Science 2 (2022).

- ⇑ PROFOR.

- ⇑ WildAid, “The Congo Basin is Under Threat – Here’s Why We Need to Act Now,” March 29, 2023.

- ⇑ Richard Eba’a Atyi, François Hiol Hiol, Guillaume Lescuyer, Philippe Mayaux, Pierre Defourny, Nicolas Bayol, Filippo Saracco, Dany Pokem, Richard Sufo Kankeu and Robert Nasi, eds., Les forêts du bassin du Congo : État des Forêts 2021 (Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 2022), 3-35.

- ⇑ WildAid.

- ⇑ Charles Doumenge, Florence Jeanne Sarah Palla, and Gervais Ludovic Itsoua Madzous, eds., Aires protégées d’Afrique centrale – État 2020 (Yaoundé: OFAC-COMIFAC, 2021).

- ⇑ Hein de Wilde, “How Satellite Data Is Used to Detect Deforestation,” Meteory (Blog), September 19, 2023.

- ⇑ Kelley Hamrick, Kim Myers, and Alice Soewito, “Beyond Beneficiaries: Fairer Carbon Market Frameworks,” The Nature Conservancy, 2023.

- ⇑ Charles Doumenge, Quentin Jungers, Claire Halleux, Lyna Bélanger, and Paul Scholte, “Which Regulations for Land-Use Conflicts in Rural Parts of the Congo Basin?” in Denis Pesche, Bruno Losch, and Jacque Imbernon, eds., A New Emerging Rural World: An Overview of Rural Change in Africa, Atlas for the NEPAD Rural Futures Programme, 2nd Edition, NEPAD Agency (2016), 50-51.

- ⇑ National Whistleblower Center, “Deforestation in the Congo Basin Rainforest.”

- ⇑ Denis Mahonghol and Chen Hin Keong, “Improving the Governance of Cameroon’s Timber Trade,” in Tropical Forest Update 27, no. 2, International Tropical Timber Organization (2018), 7-10.

- ⇑ Constant Momballa-Mbun, Allen Mgaza, Camilla Floros, and Chen Hin Keong, “An Overview of the Timber Traceability Systems in the Congo Basin Countries,” TRAFFIC-Central Africa, 2023.

- ⇑ National Whistleblower Center.

- ⇑ Global Witness, “Crisis in the Congo,” Article, June 20, 2024.

- ⇑ Emilia Díaz-Struck and Cecile S. Gallego, “Beyond Panama: Unlocking the World’s Secrecy Jurisdictions,” International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, May 9, 2016.

- ⇑ Global Witness, “Almost 2,000 Land and Environmental Defenders Killed Between 2012 and 2022 for Protecting the Planet,” Press release, September 13, 2023.

- ⇑ David Mora, “Press and Planet in Danger: Safety of Environmental Journalists; Trends, Challenges and Recommendations,” World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development Brief, UNESCO, 2024.

- ⇑ Marie-Ange Kalenga, “Ending Corruption, Improving Forest Governance: Why It Matters,” Fern, December 11, 2019.

- ⇑ Christina M. Russo, “New Reports from Inside Cameroon Confirm Grisly Mass Killing of Elephants,” Mongabay, March 14, 2012.

- ⇑ Manuela Andreoni, “An ‘Elegant’ Idea Could Pay Billions to Protect Trees,” New York Times, October 7, 2024.