Photo: Andrew Heavens.

After 3 years of relentless protests, Ethiopia started 2018 with rare good news. On January 3, then-Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn and his party pledged to release political prisoners and shut down the notorious Maekelawi detention center in Addis Ababa. In a 3-hour-long press conference, leaders of the ruling Ethiopian People‘s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) also took responsibility for the myriad of political challenges facing the country. The aim, EPRDF leaders said, was to foster national reconciliation and to widen democratic space. The announcement was roundly welcomed, including by a leery opposition, as a crucial step in the right direction.

A series of mixed signals followed. More than 6,000 political prisoners, including key opposition figures, journalists, and leaders of the country’s Muslim community, were released from prison. Not long after, on February 15, Hailemariam resigned saying he wanted to pave the way for reforms. It appeared that Africa’s second most populous nation was truly poised to turn a page on its repressive past. Not a day later, however, on February 16, authorities imposed a sweeping 6-month-long state of emergency. The decree was ratified by the EPRDF-controlled Parliament in a disputed vote on March 2.

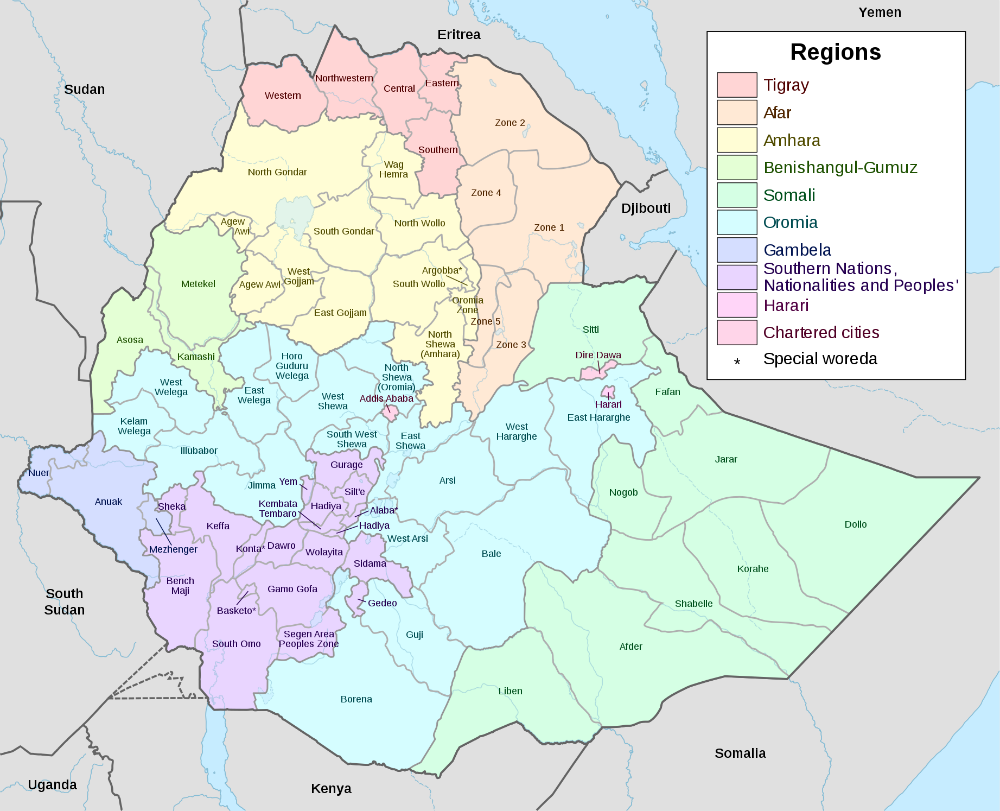

More than 60 casualties have been reported since the state of emergency came into effect. In southern Ethiopia, thousands have fled violence and sought shelter and urgent humanitarian assistance in Kenya. The latest displacement is in addition to the more than 1.2 million people internally displaced, most of them in 2017, by a tit-for-tat border conflict between Oromia and Somali States, two of the largest of Ethiopia‘s nine linguistically based regional states. The humanitarian, security, and political crises are the most serious facing Ethiopia since 1991, when the communist regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam was overthrown.

To tackle these and other challenges, the 36-member executive leadership of the EPRDF held a series of high-stakes meetings. While they agree there is a problem, they are divided over how to respond to growing public pressure and ethnic discord. As a result, once a unified vanguard party, the EPRDF is now riven by a bitter power struggle. The heightened jostling for control of the party’s policy direction has brought to the fore long-suppressed questions of inequity in the EPRDF.

How Did Ethiopia Get to This Point?

To understand the current state of flux in Ethiopia, consider the EPRDF’s history. Founded in 1989, the EPRDF is, in theory, a coalition of four ethnically based political organizations: the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), and the Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM).

Regions of Ethiopia. Photo: NordNordWest.

At the time of the EPRDF’s founding, Mengistu Haile Mariam’s communist regime was on its last leg. The Cold War was coming to an end. Having set its sights on political power in Addis Ababa, the TPLF, which had led the armed insurgency against Mengistu, needed partners to cross into the vast region south of its base in northern Ethiopia. So it orchestrated the creation of the ANDM, the OPDO, and later the SEPDM.

Once the EPRDF came to power, a multinational federation, which promised self-determination for every nation, nationality, and people in Ethiopia, was forged as a compromise between ethnonationalists and unionists who favored a centralized Ethiopian polity. This approach, explicitly organizing the Ethiopian state along ethnic lines, was a stark departure from the emphasis on a single Ethiopian national identity promoted by the Mengistu regime and Emperor Haile Selassie before it. The 1995 Constitution called for decentralization and a significant degree of self-rule for states, promises that remained largely on paper.

From the beginning, the EPRDF proved to be a coalition of unequal partners. For example, each member party has 45 representatives in the powerful 180-member EPRDF Council, even though ethnic Tigrayans constitute just 6 percent of the country’s population. Moreover, the TPLF enjoys absolute control of the military and the security establishment as well as key economic sectors. The TPLF also controlled the office of Prime Minister until 2012, and the Foreign Ministry until 2015.

The power imbalance gave rise to charges of undue Tigrayan influence over the country’s political life. TPLF leaders vacillated between acknowledgement and entitlement, given the party’s outsized role in liberating Ethiopia from the tyranny of the Mengistu regime. The ascendancy of the minority Tigrayans displaced from power the more populous Amhara, who had played the dominant role in Ethiopian political life for most of the previous century.

This Tigrayan dominance was further fortified through strict party discipline known as democratic centralism, which encouraged constituent parties to engage in vigorous internal deliberations but mandated all to adhere to the ruling party’s policy direction once a vote was taken. Moreover, as EPRDF leaders have acknowledged, the TPLF maintained covert influence inside the EPRDF by propping up and empowering loyalists. These grievances gradually gave way to growing resentment against the TPLF and, more recently, ethnic Tigrayans.

The Context of Ongoing Protests

The Ethiopian protests are the culmination of a long-building series of grievances. After the disputed 2005 elections in which the EPRDF resorted to brutal violence to maintain power, the party embarked on a developmental state model, characterized by active state intervention in the economy as a way to boost its political legitimacy. But this effort was accompanied by a heightened muzzling of critics and the media as well as controlling access to information. It also meant the institutionalization of the instruments of repression.

Ethiopians in May 2014 protest against the killing of Oromo students and expansion of the city into Oromo land. Photo: Gadaa.com.

While the EPRDF faced some level of opposition at every turn in its 25-year rule, the floodgates opened in 2014 when the Oromo, the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, began protesting against the government’s land policy. The protests coalesced around a single Oromo axiom: “The matter of land is the matter of life.” The specific trigger was an urban master plan, which sought to expand Addis Ababa’s physical boundaries deep into the surrounding Oromia State. Surprisingly, the first sign of resistance came from within the OPDO, a one-time docile party seen among the Oromo as the TPLF’s puppet.

The EPRDF seemed to be caught off guard by the scale of the protests. Security forces responded to largely peaceful protests using disproportionate force. This engendered more outrage and protests. Many dozens of people were killed and thousands arrested.

Protests briefly subsided ahead of the May 2015 national elections, in which the EPRDF and its partners claimed 100 percent of the seats in Parliament. However, Oromo protests returned when authorities attempted to forge ahead with the Addis Ababa expansion plan. A massive security dragnet ensued, leading to the deaths of even more people and the arrest of tens of thousands. By then, the initial opposition to the “land grab” and concerns over the dispossession of Oromo farmers from Addis Ababa had grown to include protesting historic Oromo marginalization, the lack of freedom and economic opportunities, and demanding the release of political prisoners.

Under pressure, authorities shelved the urban master plan and made other cosmetic changes, including a cabinet reshuffle, which saw Tigrayans ceding control of the Foreign Ministry. But EPRDF leaders left popular demands for greater democratic rights, equal economic opportunities, and state autonomy virtually untouched.

In October 2016, the protests were curbed with the declaration of a state of emergency. When martial law was lifted 10 months later, the protests returned evermore vigorously. Crucially, the protests had by then spread to other regions, particularly Amhara State and a number of localities in the southern region.

Some of the grievances were localized but the overarching theme was the same: the gap between constitutional guarantees for democracy versus the existing centralized state and authoritarian party that controlled all aspects of life. For example, in Wolkait, an administrative district in Tigray State, ethnic Amharas wanted to be part of the Amhara State and send their children to school in Amharic. A two-decade effort to settle the matter through legal and political means was repeatedly frustrated. Those frustrations fed into wider resentment over Tigrayan hegemony.

Photo: Elvert Barnes.

In Oromia, the epicenter of the opposition, the OPDO faced a legitimacy crisis. It was buckling under the weight of protests and accusations of corruption and incompetence from other EPRDF partners. This pressure helped bring to power a new generation of OPDO party cadres who were not wedded to the legacy of armed struggle. They made bold overtures to Oromo nationalism and embraced most of the protesters’ grievances, vowing to reform their party and the EPRDF to address the Oromo question or to join the protesters if their reform efforts failed.

As the OPDO positioned itself as a quasi-opposition party, the TPLF was also trying to clean its own house. Facing inevitable decline and waning influence, the TPLF held a 35-day-long evaluation session in October 2017 that culminated in demotions of top party officials and a rare public display of self-criticism.

It is against this backdrop that EPRDF leaders, in large part to meet the OPDO’s demands, agreed to free political prisoners in January 2018. The freed prisoners were welcomed by a groundswell of public support and homecoming celebrations.

“Some of the grievances were localized but the overarching theme was the same: the gap between constitutional guarantees for democracy versus the existing centralized state and authoritarian party that controlled all aspects of life.”

It is also important to recognize the leading role that youth, having come of age under the EPRDF’s one-party rule, have played in the protests. This underscores the major demographic transformations that have accompanied the calls for change. Ethiopia had an estimated total population of 52 million in 1990. It is now projected to be over 105 million with more than 70 percent of the population under the age of 30. Simultaneous to this was a rural-to-urban migration of young people. However, the pace of local job creation has not matched the number of college graduates. The influx in mobile phone usage and improved access to communications technology, meanwhile, means that this generation is far more connected to one another and to the outside world than any before it. These factors have all contributed to the resiliency of the protests.

The Way Forward

The EPRDF and, indeed, Ethiopia are at a crossroads. Resilient demands for greater freedom, equity, and opportunity indicate that the status quo is untenable. Reliance on military and security measures to quell opposition have proven futile. The EPRDF’s diagnosis of the problem in January was largely correct: the answer to Ethiopia’s malaise is greater democratic space and national reconciliation. This will require vacating the emergency decree, which has proven counterproductive to the party’s stated reform plans. It will also be necessary to address the root problems: the inequity within the governing coalition and the need for legitimacy.

A priority for reestablishing stability, therefore, should be to engage opposition parties in good faith negotiations setting forth a path for genuine popular dialogue and reconciliation. This process would entail freeing all political prisoners and setting in motion legal and political reforms to undo some of the most coercive measures that have brought the party and country to the precipice of collapse. These reforms would include the repeal of the Freedom of the Mass Media and Access to Information Proclamation, the Charities and Societies Proclamation, and the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation. These sweeping pieces of legislation have been used to curtail opposition activities, muzzle independent journalists, and silence government critics.

“A priority for reestablishing stability, therefore, should be to engage opposition parties in good faith negotiations setting forth a path for genuine popular dialogue and reconciliation.”

Through heavy state involvement in the economy, Ethiopia has registered modest growth over the last decade. Events of the last several years illustrate that this authoritarian developmental model has backfired and is coming to a dead end. Continued efforts to subdue an increasingly restive population through repressive measures now risk unraveling the economy and the country‘s fragile federation.

It is remarkable that despite the mounting grievances, the protests have largely remained peaceful. This suggests the crisis can be resolved without widespread instability. However, the continued tug-of-war between protesters and the security sector is testing public patience. It will also embolden those who insist on armed rebellion as the only way to bring about change—a quintessential story for Ethiopia, which in its long history has never had a peaceful transfer of power.

All parties committed to Ethiopia’s stability should emphasize that only genuine dialogue and reform can avert a further deterioration.

Mohammed Ademo is a freelance journalist and a Horn of Africa analyst.

Africa Center Expert

- Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 23, 2018.

- Mohammed Ademo and Hassen Hussein, “A Placeholder Prime Minister Departs. What Comes Next?” New York Times, February 18, 2018.

- Joseph Siegle, “Constitutional Design: Vital but Insufficient for Conflict Management in Africa,” Ethnopolitics, Spring 2016.

- Joseph Siegle, “Why Term Limits Matter for Africa,” International Security Network, July 3, 2015.

- Steven Livingston, “Africa’s Information Revolution: Implications on Crime, Policing, and Citizen Security,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Research Paper No. 5, November 2013.

- Joseph Siegle, “Managing Volatility with the Expanded Access to Information in Fragile States” in Diplomacy, Development, and Security in the Information Age, Shanthi Kalathil, ed., 2013.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Africa and the Arab Spring: A New Era of Democratic Expectations,” Special Report No. 1, November 2011.

- Clement Mweyang Aapenguo, “Misinterpreting Ethnic Conflicts,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 4, April, 2010.

More on: Democratization Identity Conflict Security Sector Governance Ethiopia Horn of Africa