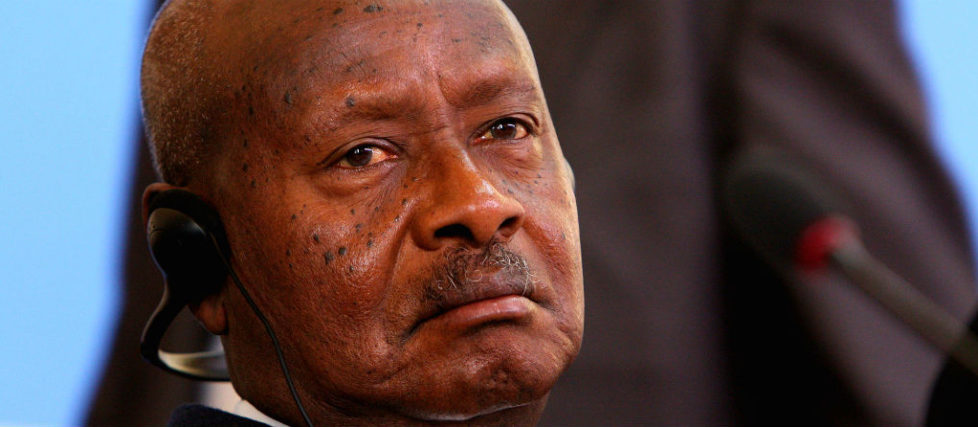

Uganda has just held its 5th presidential election since Yoweri Museveni came to power in 1986. During this time opposition parties have gained a growing share of seats in parliament. Yet, the 2016 electoral process has been marked by arrests of opposition candidates, blockage of social media sites, and charges of voting irregularities. To assess these developments in the context of Uganda’s broader democratic trajectory, six institutional factors bear monitoring.

1. The Changing Face of the Opposition

Since Museveni came to power after waging a series of armed struggles—first against Idi Amin, and later Milton Obote and Tito Okello—Uganda’s traditional opposition parties have withered away. In their place are parties that have emerged from ruptures in the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM). This is significant since many analysts contend that genuine democratic competition in Africa will only emerge from within their long dominant liberation movements.

The largest of Uganda’s opposition parties, Kizza Besigye’s Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), is making its fourth attempt against the NRM. It has increased its vote in every election except for the 2011 polls. The FDC taps into discontent with the NRM, especially among unemployed youth and participants in the informal economy—two constituencies that have not seen the benefits of Uganda’s economic growth of the past two decades.

New patterns of fundraising have also emerged. While Besigye raised the least amount of money among the three leading candidates, almost all came from small donations. Says the FDC leader, “We had very poor people giving us 10 shillings here, 500 shillings there, coins, food, animals … furniture … and all this with so much emotion.” In short, political party development, a vital feature in democracies, may be a sign of Uganda’s democratic maturation.

Christopher Clapham notes that in the transition from liberation movement to government, the legitimacy of the movement begins to wane among the public much sooner than leaders recognize. This is especially the case among the younger generation, which was not involved in and has no memory of the liberation struggles. The youth of today are therefore more motivated for a “new liberation” when facing grievances. Uganda is the youngest country in the world: More than three-quarters of the population is under 30 years old, and half is under 15. Uganda’s demographic composition, which mirrors trends elsewhere in Africa, will significantly shape the dynamics of political competition for decades to come.

2. Confidence in the Electoral Commission

As in previous elections, the composition and operation of Uganda’s Electoral Commission (EC) has been a source of heated disputes. A survey of public attitudes conducted a month before the polls found that the Commission suffers from perceptions of lack of independence and inefficiency; 89 percent of those polled wanted to see reforms in at least one aspect of the electoral process, including the Commission.

Although the Ugandan Constitution and legal code provides for the Commission’s independence, commissioners are appointed by the president, which erodes confidence in the institution’s autonomy. Other factors fuel this perception.

First, its budgetary allocations are insufficient to fulfill all of its mandated tasks. These shortcomings are especially evident in failures to adequately address voter harassment and intimidation.

Second, as in previous elections, discrepancies in voter registration were common. These include duplicate names, missing names, and names registered in the wrong district. A week before the polls, the Citizens Coalition for Electoral Democracy in Uganda, a network of 600 civil society organizations, called on the EC to correct several discrepancies in the National Voter Register, including inflated numbers of registered voters.

Third, the voting process suffered delays and complaints of vote rigging in some stations.

Reviews of global and African democratization experiences point to the indispensability of independent electoral commissions to create the legitimacy that elections are intended to generate – and ensure stability in their aftermath. The integrity of Ghana’s electoral commission is widely credited with the popular acceptance of hotly contested elections in 2008 and 2012. The perceived biasness of Kenyan’s electoral commission in the 2007 elections, on the other hand, contributed to the extensive violence that followed.

3. Youth Militias

The mobilization of youth militias by the ruling party has been a feature of past Ugandan elections. However, opposition parties have also called on this tactic in the 2016 elections. Besigye’s FDC says it recruited ten youth per village, the so-called “Power 10,” to “secure its votes on polling day” and “be vigilant,” a move that provoked warnings from the army chief. Other opposition-aligned youth groups include the so-called “TJ Solida” and the “Red Top Brigades,” which activists say have been formed in response to the announcement by presidential advisor, Major Roland Mutale, that he had trained NRM cadres to “crush anyone standing in the way of Museveni’s road to State House.” Mutale has been accused of training militias that were implicated in acts of violence in previous elections. For its part, the NRM has recruited so-called “crime preventers,” a volunteer youth force managed by security agencies to “report on and prevent crime.” Members of the force allegedly wear ruling party colors and are thought to number between 500,000 and 1 million.

This reliance on youth militias also reflects a broader trend in Africa – most recently on display in neighboring Burundi via the deployment of the government-sponsored Imbonerakure.

The political implications of this trend in Uganda are worrisome. Two-thirds of Uganda’s unemployed are under 30 years old, creating a sense of disenfranchisement. This makes them especially vulnerable to political manipulation. “Many will seek employment, integration into the security forces, and other rewards for their role in the elections,” says a leading human rights lawyer. “This will be a challenge regardless of who wins.”

4. Neutrality of the Security Forces

The government says it has deployed up to 150,000 forces from the police, army, and intelligence community in support of the 2016 elections. In previous polls security forces were able to contain violence, including in 2011 when a month-long protest emerged immediately after the elections. This year, they broke up several opposition rallies in the run-up to the election and as vote-counting started, Besigye was arrested three times in the week of the election. Military professionalism is essential for democratic development and the Uganda People’s Defense Forces (UPDF), which is respected by most Ugandans, has performed better in this regard than previous Ugandan armies. However, the legacy of political and ideological education at all levels of the force continues, prompting complaints by some that it is vulnerable to political maneuvers. The NRM insists that political education of the military has defeated the sectarian thinking that was prevalent in previous armies and improved the relationship between the army and civilians. Yet, if the elections are disputed it could expose the military to perceptions of bias and damage its hard-earned reputation. The active presence of the “crime preventers” as a government-trained but non-statutory youth militia also confuses the role and integrity of Uganda’s security forces.

5. Independence of the Courts

The judiciary has been relatively independent in previous elections. In 2001, Besigye lost a petition at the Supreme Court to nullify the election result. The ruling was narrow, as two of the five judges held that the elections should be nullified. Moreover, all five found that there was interference with ballot boxes in several polling stations, as alleged by Besigye. In 2006, an identical ruling was delivered, this time by a four to three decision and, like in 2001, all judges agreed that the polls were marred by irregularities. “Many Ugandans see a ray of hope in our judiciary,” says a retired judge and top constitutional lawyer. “Of course, we still have problems in the administration of justice, but as is the case in other countries, many of these problems have a lot to do with shortcomings in the political process as a whole.”

The judiciary exhibited its autonomy again in 2011 after Besigye called for a civil uprising to protest the election result. He was arrested four times but all charges were dropped as the courts ruled that the public had the right to hold demonstrations. Many Ugandans attribute much of this independence to the Ugandan judiciary’s traditional reputation as an institution of high standing, with members who have distinguished themselves at home and abroad over the years. This credibility may prove vital for resolving any conflicts that emerge from the 2016 electoral process.

6. Media and Information Technology

While this election has not been free of media interference and censorship, the Ugandan media offers opportunities for multiple voices to thrive in national debates. Uganda has 240 private radio stations and dozens of print publications and TV stations. Meanwhile, recent trends could positively impact future elections. The holding of two presidential debates was a first in the country’s history. Social media has become an important medium in the electoral process. While President Museveni did not participate in the first debate, he joined other presidential candidates for the second one. During that debate Uganda ranked fifth most active country on Twitter with 3 million Ugandans tweeting that day.

Democracies require access to independent information so that citizens can be informed—and hold political office-holders accountable. Uganda’s progress in this area—a pattern seen in other African countries—bodes well for its democratic development.

In sum, beyond the vote totals of Uganda’s competing presidential candidates, Uganda’s democratic progress is ultimately dependent on shoring up the institutions on which not only elections but day-to-day democratic governance relies. This review reveals a mixed record. How these institutions manifest themselves in the post-election period will greatly shape perceptions of how far Ugandans’ democratic aspirations still have to go.

Additional Resources

- Nicole Amani Mugabo, “Museveni’s ‘Babies’ want Change in Uganda this Election, so they’re Running for Office,” Quartz Africa Weekly, February 14, 2016.

- Electoral Institute of Southern Africa (EISA), “Preventing and Managing Violent Election Related Conflicts in Africa,” Conference Report of EISA’s Fourth Symposium, November 2009.

- Gilbert Khadiagala, Khabele Matlosa and Nour Eddine Driss, “Election-Related Disputes and Political Violence: Strengthening the Role of the African Union in Preventing, Managing, and Resolving Conflicts,” Report of the African Union Panel of the Wise, July 2010.

More on: Uganda