Download this Security Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

The increasingly internal nature of Africa’s security threats is placing ever greater pressures on Africa’s police forces. Yet severe resource and capacity limitations, combined with high levels of public distrust, leave most African police forces incapable of effectively addressing these expanding urban-based threats in the near term. This Africa Security Brief examines the potential of nonstate policing organizations—community-based groups with local credibility and knowledge—to help fill this gap.

Highlights

- Worsening urban violence is placing increasing demands on Africa’s police departments.

- African police forces are typically woefully underresourced, inadequately trained, unaccountable, and distrusted by local communities, leaving them ineffective in addressing these security challenges.

- Nonstate or community-based policing groups often enjoy local support and knowledge, accessibility, and Accordingly, collaborative state-nonstate policing partnerships represent an underrecognized vehicle for substantially expanding security coverage in Africa’s urban areas in the short term at reasonable cost.

The Threat of Urban Crime in Africa

Violent crime in Africa’s cities is endemic and in many places worsening. Africa as a whole has a homicide rate of 20 per 100,000 (in Europe it is 5.4, in North America 6.5, and in South America 25.9).1 The problem is particularly severe in some urban areas. Kinshasa’s homicide rate is estimated to be as high as 112 homicides per 100,000. The Nigerian police have recorded consistently rising rates of murder and at- tempted murder over the last 20 years.2 Rates of armed robbery in Africa are also very high. In Nairobi, 37 percent of residents reported being victims. The rate is 27 percent in some Mozambican cities and 21 percent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).3

Research at a Cape Town hospital revealed that 94 percent of patients had at some point faced exposure to violence.4 South Africa Police Service figures also show an alarming rise in sexual crimes, with 27 percent of men indicating they had committed rape.5

Whatever the accuracy of crime statistics in Africa, the perception of growing danger has generated widespread anxiety. In Lagos, Nigeria, 70 percent of respondents in a city-wide survey were fearful of being victims of crime.6 In Nairobi, more than half of the citizens worry about crime “all the time” or “very often.”7 A World Bank study in Zambia uncovered such a significant fear of crime that it affected the work decisions of teachers.8 Anecdotal accounts among city dwellers across Africa indicate that urban crime rates have increased rapidly in the last two decades, contributing to pervasive fears that impede commerce, fray social capital, and undermine normal urban activity. Violent crime is a daily threat for many city dwellers.

Such high crime rates have many contributing factors. To a large extent they are not surprising given Africa’s poverty coupled with its proximity to wealth in cities. The continent’s many protracted conflicts have also undoubtedly played a role. Many African cities have either directly faced war or suffered the social and economic consequences of conflict elsewhere in the country. These conflicts have produced violent political cultures and have traumatized, divided, and further impoverished societies. They have also fostered the availability of firearms. The percentage of city households claiming to own firearms in 2005 was 18.3 in South Africa, 22.1 in Namibia, 31.1 in the DRC, and 56.3 in Burundi.9

“the growing threats to stability posed by these internally focused security challenges underscore the expanding importance of Africa’s police forces for national security”

Global processes also lie behind Africa’s rising urban crime. While the continent’s growing integration with international trade has introduced new commodities and market opportunities, it also has attracted illicit businesses, protection rackets, smuggling, and money laundering. New understandings of acceptable practices of livelihood formation have accompanied rising organized crime.10 Now, the path to success is often perceived as having less to do with education and hard work than with criminality, illicit deals, and trickery.

Africa’s weak security services and large numbers of unemployed or underemployed people desperate to earn a living make it an attractive base for international criminals. The United Nations (UN) Office on Drugs and Crime has identified West Africa, with its ineffective policing and bribable governments and security forces, as an emerging narcoregion that provides a convenient halfway stop for Latin American drug traders exporting to Europe. Such international crime offers insurgents, militias, extreme political groups, and terrorist organizations opportunities for financing their activities. For instance, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) is reported to allow, at a price, heavily armed convoys transporting drugs from West Africa across territory it controls.11 Other terrorist groups based in Africa support themselves by kidnapping.

The upsurge in urban crime is aggravating other sources of instability. It deters the building of sustainable political institutions, economic growth, and social reconciliation.12 High crime rates similarly undermine trust in and respect for government, con- straining its ability to provide leadership and foster popular participation. These concerns, in turn, depress both domestic and international investment and further weaken economic prospects.

The growing threats to stability posed by these internally focused security challenges underscore the expanding importance of Africa’s police forces for national security. Indeed, there is a growing recognition that Africa’s security forces need to be realigned toward the police to better meet its contemporary internal security challenges.

The Weakness of Africa’s Police

The sobering reality, however, is that the police in Africa have not had great success in dealing with urban crime. A difficult environment, the police force’s traditional disinterest in the poor, and lack of resources both in terms of personnel and in skills and equipment hamper its ability to be effective.

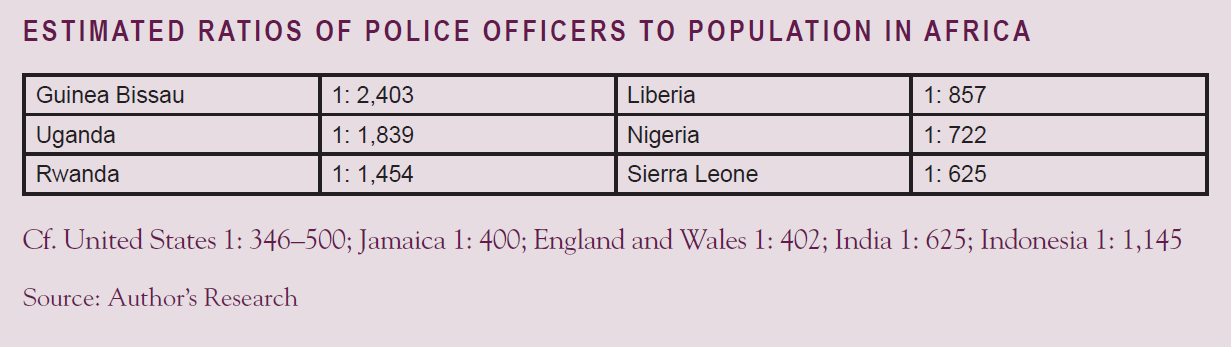

Too often police presence in the high-density locations where most city dwellers live is only sporadic and the number of officers available is very small (see table 1). Those who are available are commonly undertrained and may even lack literacy skills. Moreover, African governments often severely lack resources, institutional capacity, and in some cases control of territory. Available resources have commonly been tilted heavily toward the military over the police. This preference for the military has weakened the police, who lack management and technical skills, interagency coordination, communication equipment, transport, and even lighting, office space, filing cabinets, stationery, computers, uniforms, and forensic labs—all undermining effectiveness.

Compounding these challenges is a long history of police neglect, corruption, and impunity common in Africa, having its roots in part in coercive colonial policing practices. One continent- wide analysis argues that the police in most African countries are “significantly brutal, corrupt, inefficient, unresponsive and unaccountable to the generality of the population.”13 Indeed, multiple reports from Amnesty International, the International Bar Association, the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, and other respected international research institutes have frequently documented and criticized police behavior across the continent.14 Afrobarometer data found that only a minority of citizens in countries such as Benin, Zambia, Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya trusted their police force “a lot” or “somewhat.”

When police agencies in Africa are working in postconflict situations, they face an even tougher environment. Commonly, in the immediate aftermath, it is found that police personnel have abandoned their posts, been killed, or are no longer suitable for further employment because they committed human rights abuses. For instance, during Sierra Leone’s civil war approximately 900 police officers were killed and a considerable number suffered amputation. As a result, the size of the police force was reduced from 9,317 to 6,600.15 For years after the civil war, police commanders across Sierra Leone reported a serious lack of officers, vehicles, land phones, and accommodation for the officers.16

Thus, in a postconflict situation there is a double dilemma. On the one hand, mechanisms of social order have been undermined, poverty has been exacerbated, and there is a surfeit of weapons and unemployed excombatants. On the other hand, the available resources and security personnel have been reduced, and respect for the agencies may have been diminished still further because of conflict abuses.

Many African governments have introduced new police restructuring, training, and oversight bodies but with limited success. Accordingly, few citizens expect a rapid transformation of policing and police forces. Rather, many continue to doubt their governments’ ability and willingness to finance the necessary steps that promise police availability, accountability, integrity, effectiveness, and community partnership. Their skepticism is reinforced by continuing media accounts of police abuse and collaboration with criminals and citizens’ daily encounters paying bribes to police to allow them through traffic check points17 or to investigate crimes.

“…[there] is a long history of police neglect, corruption and impunity in Africa…””

This experience has driven many citizens to look elsewhere for protection. As one Nairobi citizen said, “If you do not make an extra arrangement for security beyond what the state provides, then you are vulnerable to attacks.”18 In short, official police protection is insufficient to address the growing violence experienced in many African cities. Even local police commanders recognize the need to supplement their weakly performing personnel.

Policing by Communities: Unrecognized Providers

While police in Africa’s cities are almost invariably weak and underresourced, citizens are not with- out policing services. In fact, such services are widely available to the majority—but they are provided by nonstate actors. In Africa it is not always appreciated that nonstate actors are so numerous and diverse that they are the dominant police providers, often enjoying local ownership, cultural relevance, accessibility, sustainability, and effectiveness. It is estimated that more than 80 percent of justice services are delivered by nonstate providers in Africa.19

The nonstate sector is so diverse that generalizations, whether dismissive or laudatory, are not useful. Africa’s numerous policing providers include customary leaders, religious organizations, ethnic associations, youth groups, street associations, work-based associations, community police forums, neighbor- hood organizations, local and international security companies, and local entrepreneurs. Contrary to popular opinion, not all are militants or vigilantes prone to violence and abuse. Indeed, they are often the preferred police in Africa’s cities. A survey of four Nigerian states found 16 nonstate policing organizations dealing with crime, which were citizens’ preferred choice 38 percent to 89 percent of the time.20

“in Africa it is not always appreciated that nonstate actors are so numerous and diverse that they are the dominant police providers, often enjoying local ownership, cultural relevance, accessibility, sustainability, and effectiveness”

Nonstate police are for the most part within walking distance, speak local languages, and do not use formal legal terminology or procedures. A response is more or less guaranteed, thus making them more familiar and accessible. Required payments are usually relatively small. With their local knowledge, they commonly resolve neighbor disputes, restrain antisocial behavior, protect homes at night, and return stolen goods more consistently and effectively than official police. And they are culturally relevant in that they are policing the local prevailing norms about what is a crime and how it should be addressed so as to restore community harmony. They exist not just because the state police are ineffective in enforcing order, but because the police are often perceived as enforcing an alien, inappropriate, or erroneous order.

Undoubtedly, some of the criticisms of local nonstate actors are valid. Some are indeed prone to human rights abuses and may be unreliable, have poor skills, and lack both transparency and vertical accountability. Yet most are not violent autonomous groups but frequently civic-minded, concerned citizens who regularly collaborate with African police forces.21 Such links are often welcome on the part of the local police commanders because they are unable to fulfill all of their responsibilities without local assistance. For nonstate actors, despite their awareness of the failings of the police, links with the police offer legitimacy and access to resources. They may also help ensure the police are more efficient and accountable. Typically collaboration involves sharing intelligence, equipment, training, and operational responsibilities.

Collaboration between state and nonstate police is common in African cities. The Rwandan government has authorized volunteers at the lowest level of local government to undertake everyday policing. Thus, they are frequently the policing agents of first choice. These authorities keep records of strangers to neighborhoods, report deviant behavior to officials, undertake dispute resolution, conduct patrols, and investigate minor crimes. Operating in such a restricted area of perhaps no more than 50 to 200 households might seem to be excessive state surveillance that can be hijacked for political ends. On the other hand, according to local surveys, it does reduce urban crime remarkably.

Faced with rising armed crime they could not contain, the Liberian police, in consultation with community leaders, have established security zones in Monrovia each with their own local watch teams. The teams patrol the suburbs at night, sometimes with the police, frequenting areas few police are willing to patrol by themselves. Working with the police, watch team violence against criminals has been re- strained and police presence extended.

A southern Sudan market association in Yei has arranged with the police that when any traders are arrested they are to be handed over to the association. The market association then resolves the issue and reports their resolution to the police. While such an arrangement may obscure due process, it is regarded as a success by both the police in reducing their work load and by the association in preventing the escalation of relatively small disputes into the slow and expensive criminal justice system.

Another work-based organization, the taxi-driver’s association in Uganda, has an agreement with the police that allows the association to police taxi and bus parks regarding traffic offenses, pickpockets, and disputes between drivers and passengers. For their part the police offer the associations’ members training in crime control. When last surveyed it was seen as working in the interests of all.

Turning from informal groups to the commercial sector, a state–private sector partnership arrangement has produced positive results in Cape Town, South Africa. City center policing is run by Cape Town Partnership, which is an organization established and controlled by the city council and the business community. Private security guards patrol the area and secure public spaces in the city center. They maintain contact with the city police control room by radio and also supervise the area’s closed circuit television (CCTV). There are concerns that this approach merely displaces crime and that “undesirables” such as street merchants, the homeless, and beggars are “criminalized.” Nevertheless, the program is seen as a great success in creating a more secure city center and an attractive investment and tourist destination.

These are not isolated illustrations. Across Africa’s cities a large variety of actors provide policing, many in informal (and sometimes formal) partner- ships with local police. Commanders of local police who participate in such collaborations recognize that nonstate actors present opportunities to enhance police effectiveness and institutional reputation. Further, one can argue that in the case of commercial security, they guard the principal economic assets of many African cities—banks, hotels, factories, inter- national organizations, embassies, and even government and UN buildings. The stability gained, in turn, encourages further economic development.

It is true that nonstate actors lack the resources and skills to address international crime. Their contributions toward everyday policing, however, afford the official police greater latitude to redirect some of their resources to the threats of international and organized crime. Nonstate actors also offer the police a vital intelligence network of such criminal activity. Moreover, inasmuch as nonstate policing extends acceptable security provision, it promotes social equity, the lack of which is often argued as a contributing factor in the rise of crime. In short, there are sufficient success stories of nonstate policing at the local level to suggest that innovative national frameworks for security partnerships between state and nonstate actors can be used widely and systematically for ad- dressing rising urban crime in Africa.

A Program to Tackle Urban Crime

Programs for addressing urban crime in Africa must take into account two facts: One, the state police are too weak to undertake the task of crime prevention and investigation by themselves. Two, there are in fact many nonstate actors who currently provide the majority of everyday policing in cities. To establish a state police service sufficiently large and equipped to serve all citizens would take years and would be beyond many African state budgets to achieve or to sustain. Conversely, supporting nonstate actors already on the ground and who meet certain standards is much less costly and likely to be more sustainable. What is needed, then, is a coordinated program of targeted assistance for community-based and commercial nonstate policing in addition to the support given to state policing.22

Such a program would not need to start from scratch with unfamiliar actors but could draw on existing though often overlooked successful local partnerships that contribute tangible results and efficiencies. By facilitating such partnerships, international donors can also help address concerns of poor and marginalized communities that make up sizable portions of Africa’s growing urban areas. Partnerships also prevent nonstate actors and state police from being totally autonomous and acting with impunity. Through semiformal partnerships, nonstate actors more often integrate and conform to generally accepted policing standards.23

“…inasmuch as nonstate policing extends acceptable security provision, it promotes social equity, the lack of which is often argued as a contributing factor in the rise of crime”

State-nonstate policing partnerships also boost efficiency and performance. Some might fear that support to nonstate actors will divert precious re- sources away from formal policing. However, most nonstate actors require fairly minimal support. They do not use expensive buildings, computers, and vehicles or pay high salaries. A small investment in nonstate actors produces benefits for the state police in terms of increased personnel on the ground and enhanced intelligence. Moreover, this can be done alongside state police capacity building initiatives. As such, it constitutes no significant threat to police productivity. On the contrary, partnership permits a division of labor where the police can concentrate on their most essential functions and make use of their special skills, authority, and expertise while nonstate actors can undertake their own low-level and everyday policing needs (with backup support from state police in cases where they cannot cope). To better capitalize on these advantages, several priority steps should be taken.

Know the actors and set benchmarks for partner- ship. It is vital first to map nonstate policing groups, for it is not always obvious who is working in the field, what they are doing, and how. From such a mapping exercise it is important to identify the policing groups who should be supported. Reliable and effective non- state partners will be those groups most open to reform and, above all, those that enjoy widespread local sup- port. Nonstate police actors will perform best when they are perceived as legitimate and effective by those they are policing. However, the bar of acceptability should not be set so high as to require a nonstate group to meet current international standards. After all, few police forces in Africa would qualify by that criterion. What is important is that a policing group has local credibility, is not criminal or abusive, and is open to reform.

Devise performance guidelines and supervisory mechanisms. An overarching framework of policing standards to guide performance, procedures, jurisdictions, interventions, and other regular activities of nonstate policing actors should be developed. An accreditation program that acknowledges demonstrable knowledge and skills of nonstate actors would also be beneficial. It could offer a degree of legitimacy to the nonstate actors and opportunities to monitor and improve their performance. Accredited nonstate policing groups that sign up to a framework of standards could also be held accountable by city-wide structures. Drawing on the Cape Town Partnership model, state police would play a city-wide supervisory and coordinating role. They would receive reports of threatening activity, request a response from nonstate policing groups, and determine when the situation demands for the state police to be called in.

It is important to acknowledge that it is not just the nonstate actors that should have their standards raised. The skills of both partners need to improve. Both sides are then likely to increasingly respect and trust one another and both will gain the support of the people when they demonstrate that they are responsive to local needs and skilled in their respective areas of specialization. This would entail nonstate actors solving routine local problems of crime and disorder. The police, in turn, will focus on specialized or more complex criminal investigations and handling major problems.

Police urban crime hotspots that are ripe for partnership. A valuable first step in cities would be to seek solutions in two principal urban crime hotspots—markets and taxi-bus parks. Nonstate groups with a vested interest in maintaining order are already active in these areas. The range of economic activity and density of people frequently cause higher crime rates, and police and groups such as traders’ and drivers’ associations need to be brought together to better police these hotspots. State-nonstate partners can organize an agreement on division of labor, training programs in the law and its enforcement, and cooperative forums so as to enhance security in these key urban areas.

Conclusion

Policing programs exclusively focused on re- forming state providers—when a state has very limited capacity—are unlikely to meaningfully enhance security for Africa’s cities in the near term. Account has to be taken of the many nonstate actors that offer everyday policing in the field. Police collaboration with acceptable nonstate actors offers an affordable and sustainable way to extend urban policing. Put another way, partnerships with the right nonstate actors enable African governments to extend crime protection to a larger segment of the population. Beyond enhancing local crime protection, this will increase government legitimacy, enhance social equity, and reduce the appeal of sinister organizations that prey on poverty and resentment.

Notes

- ⇑ “Global Burden of Armed Violence Report,” Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, 2004.

- ⇑Official Crime Statistics, Centre for Law Enforcement Education in Nigeria (CLEEN Foundation), available at <www.cleen. org/officialcrimestatistic.html>.

- ⇑ Robert Muggah and Anna Alvazzi del Frate, “More Slums Equals More Violence: Reviewing Armed Violence and Urbanisation in Africa,” UN Development Programme, October 2007.

- ⇑ The Trauma Center, see <www.trauma.org.za>.

- ⇑ Rachel Jewkes, Yandisa Sikweyiya, Robert Morrell, and Kristin Dunkle, “Understanding Men’s Health and Use of Violence: Interface of Rape and HIV in South Africa,” (Pretoria: Medical Research Council, 2009).

- ⇑ Etannibi EO Alemika and Innocent C. Chukwuma, Criminal Victimization and Fear of Crime in Lagos Metropolis, CLEEN, Monograph 1, 2005.

- ⇑ “Crime & Violence at a Glance,” Enhancing Urban Safety and Security: Global Reports on Human Settlements 2007 (London: UN–HABITAT, 2007).

- ⇑ Caroline Moser and Jeremy Holland, “Household Re- sponses to Poverty and Vulnerability, Volume 4: Confronting Crisis in Chawama, Lusaka, Zambia,” (Washington, DC: World Bank, 1997), 125.

- ⇑ UN Development Programme, 4.

- ⇑ AbdouMaliq Simone, Principles and Realities of Urban Governance in Africa (South Africa: UN–HABITAT, 2002).

- ⇑ Stephen Ellis, “West Africa’s International Drug Trade,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 6, 2009.

- ⇑ Charles T. Call, “Competing Donor Approaches to Post- conflict Police Reform,” Conflict, Security & Development, 2, no. 1, 110; “Post-Conflict Reconstruction Task Framework Report,” Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Association of the United States Army (AUSA), 2002.

- ⇑ Institute for Democracy in Africa (IDASA), “Conference Summary Report, Police Reform & Democratisation Conference,” IDASA, 2007, available at <www.idasa.org.za/index. asp?page=topics_details.asp%3FRID%3D11>.

- ⇑ Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, “Policing in East Africa,” 2006; International Bar Association Human Rights Institute, “Partisan Policing: An Obstacle to Human Rights and Democracy in Zimbabwe,” 2007; “Nigeria: Killing at Will: Extra- judicial Executions and Other Unlawful Killings by the Police in Nigeria,” Amnesty International, 2009; IDASA, 2007.

- ⇑ Mark Malan, Angela McIntyre, and Phenyo Rakate, Peacekeeping in Sierra Leone: UNAMSIL Hits the Home Straight, Monograph 68 (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2002), 65.

- ⇑ Bruce Baker, “Who Do People Turn to for Policing in Sierra Le- one?” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 23, no. 3, September 2005.

- ⇑ Research in 2002 showed that on average each Kenyan had been forced to bribe the police 4.5 times a month, paying them on average US$16 per month. Over 95 percent of dealings with the police resulted in a bribe. Betty Wamalwa and Atsango Chesoni, “National Integrity Systems Country Study Report: Kenya 2003,” Transparency International.

- ⇑ Pamela Leach, “Citizen Policing as Civic Activism: An International Inquiry,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 31, no. 3, 2003.

- ⇑ OECD DAC, Handbook on Security System Reform: Supporting Security and Justice, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2007; Bruce Baker, Security in Post-conflict Africa: The Role of Non-State Policing (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2009).

- ⇑ Etannibi Alemika and Innocent Chukwuma, “The Poor and Informal Policing in Nigeria,” CLEEN Foundation, 2004.

- ⇑ Baker, 2009.

- ⇑ OECD DAC.

- ⇑ Bruce Baker and Eric Scheye, “Access to Justice in a Post-conflict State: Donor-Supported Multidimensional Peacekeeping in Southern Sudan,” International Peacekeeping 16, no. 2, 2009.

Bruce Baker is a Professor of African Security at Coventry University, United Kingdom.