Download this Security Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Africa is facing an increasingly menacing threat of cocaine trafficking that risks undermining its security structures, nascent democratic institutions, and development progress. Latin America has long faced similar challenges and its experience provides important lessons that can be applied before this expanding threat becomes more deeply entrenched on the continent—and costly to reverse.

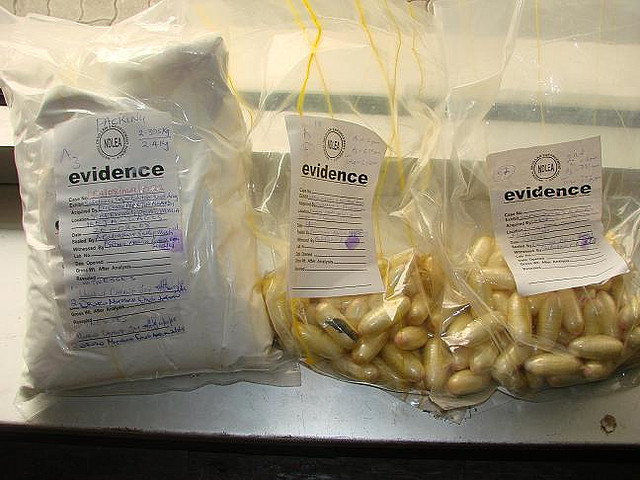

Cocaine smuggling West Africa is becoming a new transit point for drugs from South America on their way to European markets. Photographer: Dulue Mbachu and the Security Network

Highlights

- The dollar value of cocaine trafficked through West Africa has risen rapidly and surpassed all other illicit commodities smuggled in the sub-region.

- Experience from Latin America and the Caribbean demonstrates that cocaine traffic contributes to dramatically higher levels of violence and instability.

- Co-opting key government officials is the preferred modus operandi of Latin American cocaine traffickers. African governments need to act urgently to protect the integrity of their counternarcotics institutions to prevent this threat from developing deeper roots on the continent.

In November 2009, on a dry lakebed in the desert of northern Mali, United Nations (UN) investigators found traces of cocaine amidst a Boeing 727’s charred and stripped fuselage. Its owners had apparently torched the plane after it had been damaged, probably to destroy evidence of their identity and cargo. With a payload capacity of 10 tons of cocaine fetching a wholesale value of $580 million, West Africa’s emerging cocaine traffickers could afford the loss.

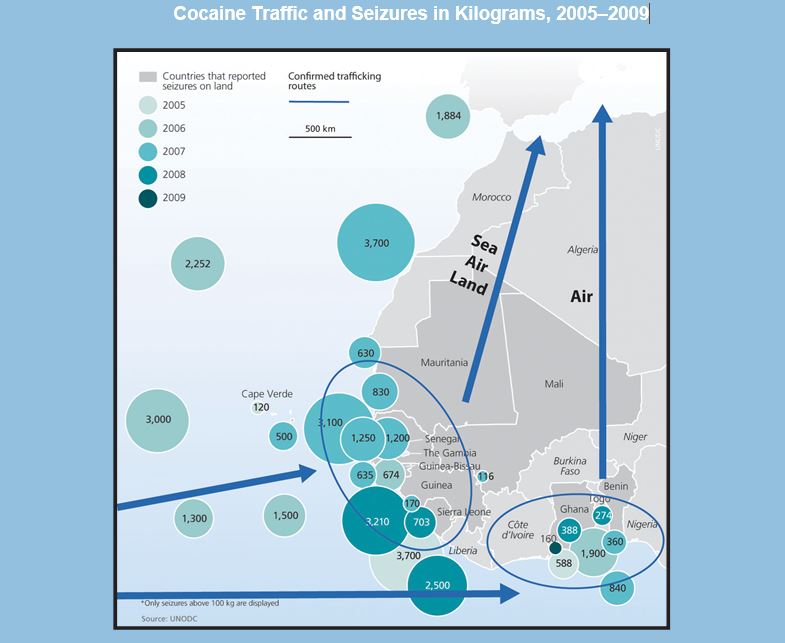

The flight path of this 727 may have included layovers in Gambia, Senegal, Guinea, and Guinea Bissau, but it assuredly originated from South America. Its cargo added to the mounting cocaine traffic from Latin America that transships West Africa on its way to European consumers. Estimates of annual cocaine transshipments in West Africa range between 60 and 250 tons, yielding wholesale revenues of $3 billion to $14 billion.

Beginning in 2006, several West African countries seized extremely large volumes of cocaine— measured in the hundreds and thousands of kilograms—in single hauls. These seizures were often accidental, indicating that actual traffic was likely much higher. Cocaine departs Venezuela, Colombia, and elsewhere in South America in shipping containers, on yachts, and by small planes and jets. South American organized criminal and militant groups commonly deliver bulk shipments to West African traffickers in Ghana, Nigeria, Guinea, and Guinea Bissau, countries that the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) frequently characterizes as the subregion’s cocaine “hubs.” The cocaine is then repackaged and moved to neighboring countries before being transferred to syndicates in Europe, often composed of African expatriates, who handle wholesale and retail sales. Seizures in West Africa have resulted in the arrests of African, South American, European, and other nationals.

While West Africa is the current locus of this activity, the continent as a whole is an ideal transshipment center—poor, with limited oversight and weak policing—making for a low-cost and low-risk environment. Since Africa is not a producer or major consumer of cocaine, some assume that its domestic effects will be minor. Yet evidence of cocaine’s destabilizing impact is already emerging. The assassinations of Guinea Bissau’s president and the head of the army in early 2009 were likely linked to cocaine transshipment. In January 2010, a senior officer of Guinea Bissau’s Presidential Security Service was arrested in a narcotics sting, prompting senior military officials to publicly lament the regular involvement of security personnel in cocaine transshipment. In late 2009, Ghana extradited three Malians who claimed links to al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb to the United States on cocaine trafficking charges. The sheer value of the trade poses not only a threat to security but also real risks of distorting the region’s economy, investment flows, development, and steps toward democracy.

“cocaine is an order of magnitude more seductive than other goods smuggled across the subregion”

Cocaine transshipment in Africa is new, but Lat- in American and Caribbean countries have over 30 years of experience dealing with narcotics trafficking and its destabilizing effects. Hard-earned lessons from Latin America’s experience, then, hold potentially invaluable insights for Africa as it engages this new, pernicious enemy.

No Ordinary Illicit Commodity

Trafficking in illicit goods is common in West Africa. Arms, counterfeit medicine, cigarettes, and crude oil all move illegally to and through West Africa. Traffickers in the subregion also have a history of smuggling heroin around the world. The “mule” method of hiring travelers to swallow narcotics in small parcels and travel by air is probably a Nigerian innovation.

But cocaine is an order of magnitude more seductive than other goods already smuggled across the subregion. Kilogram for kilogram, it is immensely more valuable. According to a UNODC assessment of trafficking in West Africa, the estimated value of cocaine transshipments in 2008 rivaled crude oil for the most valuable smuggled commodity. Yet the volume of cocaine traffic was comparatively minuscule compared to the 55 million barrels of oil that were stolen and transported for the same return.

The yields from cocaine transshipment also dwarf the subregion’s official resources. During one incident in January 2008, Malian security officials seized 750 kilograms of cocaine following a shoot- out. This one haul represented 36 percent of Mali’s entire 2007 military expenditures. Similarly, the 350 kilograms of cocaine seized on one occasion in August 2007 in Benin represented the annual per capita income of 31,000 Beninois.

Cocaine traffic may prove to be a fixture in West Africa. Transshipment has emerged in part because demand is growing in Europe. According to the UN International Narcotics Control Bureau, cocaine use has doubled and tripled in some parts of Western Europe since 2000. Traffickers, it would seem, are not shifting traffic to service preexisting demand but establishing a new route for a growing market.

Market dynamics also explain why heroin traffic through West Africa has not been nearly as destabilizing. West Africa plays a small role in global heroin traffic because consumer markets in North America and Europe are supplied through the Balkans, Middle East, and South Asia. Only 167 kilograms of heroin was recovered in West and Central Africa in 2007, or less than one-thirtieth the amount of cocaine seized in just West Africa for the same year. There are growing concerns, however, that instability in East Africa is attracting heroin traffic (contributing to an estimated 200,000 heroin addicts in Kenya), which may merge with West African cocaine routes.

Cocaine, Governance, and Corruption

Over the last decade West Africa has emerged from widespread instability and benefited from a period of declining violence and growing democracy. Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Côte d’Ivoire are emerging from civil wars. Mali, Ghana, and Benin continue to consolidate democratic gains. Cocaine traffic poses a direct threat to these advances.

Traffickers abhor attention. Any state response—whether parliamentarians passing laws to enhance border security or investigators prosecuting smugglers—raises transaction costs and lowers prof- its. Consequently, traffickers will attempt through co-optation, bribery, and corruption to prevent and deter a state’s response in order to protect their prof- its. Rather than guard cocaine cargoes with heavily armed security and gunfights, traffickers would rather pay politicians, judges, and police officers to ignore their trade altogether. The strategy is to make these officials beneficiaries early to ensure low costs over the long term.

In the Caribbean, narcotics traffic has been a major factor in expanding and deepening corruption. Jamaica has struggled for years against endemic corruption, clientelist politics, and a lack of checks and balances within government—a familiar combination in West Africa. Beginning in the late 1990s, however, its strategic location between the United States and drug-producing countries in Latin America attracted rising cocaine transshipment. By 2003, Jamaica had become a leading transit country for cocaine destined for the United States. The quality of governance on the island soon worsened. Jamaica’s ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index fell from 45th in 2002 to 99th in 2009. The sharp drop in public integrity coincides with regular efforts by transnational and Jamaican criminal groups “to corrupt functionaries in critical state agencies—particularly the police and customs—political party functionaries and grass roots, community organizations.”1

Narcotics trafficking has penetrated government and undermined governance elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 2009, Leonel Fernández, president of the Dominican Republic, dismissed 700 police and 535 military officers, including 31 senior leaders, citing links to cocaine traffic. In Mexico, the Zetas, a criminal group renowned for assassinations on behalf of drug traffickers, was formed by officers who deserted the military. In Brazil, São Paulo’s narcotics traffickers train their members to pass Brazil’s civil service exam, thereby gaining influence within the government bureaucracy.

“. . . when violence within one criminal activity rises, all crimes can become more violent . . . often, the average age of violent criminals falls and the prevalence of violent youth behavior grows. In short, a culture of violence emerges”

As cocaine transshipment grows, West Africa’s fragile governance institutions may be further weakened. African media reports and independent research already suggest that narcotics transshipment proceeds may be financing political parties and campaigns in Ghana.2 A Nigerian politician arrested before boarding a plane from Lagos to Germany with more than 4 pounds of cocaine in his stomach explained that he needed the funds to finance his upcoming election campaign. Authorities believe he may be part of a wider network of smugglers.3 In Sierra Leone, the minister of transport and aviation was dismissed after trial proceedings revealed that he allegedly provided landing clearance to a plane carrying 700 kilograms of cocaine.4 There are similar reports of senior level police officers involved in cocaine trafficking from Benin, Nigeria, and Ghana.5

Cocaine, Crime, and Violence

Narcotics trafficking is not intrinsically violent. Violence within the international trade in cannabis and Ecstasy, a popular hallucinogen/amphetamine, is comparatively low. But the overwhelming evidence from Latin America and the Caribbean indicates that where cocaine traffic moves, so too do homicide rates and conflict.

If efforts of co-optation and bribery prove unsuccessful, traffickers may resort to violence to deter or resist attempts by government authorities to curtail drug flows and arrest traffickers. Trafficking groups also use violence to maintain loyalty and discipline as well as target other traffickers to resolve disputes, enforce agreements or contracts, and protect or acquire market share. In such environments, violence can spiral. Studies have shown that when violence within one criminal activity rises, all crimes can become more violent, gangs proliferate, and frustrated citizens may resort to mob justice including lynching suspected criminals.6 Often, the average age of violent criminals falls and the prevalence of violent youth behavior grows. In short, a culture of violence emerges.

Evidence from Latin America bears this out. The homicide rate there, the highest in the world, is more than three times the global average. Guatemala’s homicide rate rose 50 percent between 2004 and 2008, an increase that paralleled cocaine traffic. According to a World Bank report on crime in the Caribbean, “The strongest explanation for the relatively high rates of crime and violence in the region—and their apparent rise in recent years—is narcotics trafficking.”7

Jamaica has one of the highest homicide rates in the world, and an estimated 40 percent of all murders are related to narcotics disputes. Indeed, there are 268 local and transnational gangs in Jamaica alone, comprising tens of thousands of members. Police shootings have correspondingly risen sharply while relations with civilians have suffered. Within the last 10 years, almost 2,000 Jamaicans have been killed by the police—slayings often followed up by the most cursory of internal investigations.

Such conditions can contribute to severe bursts of violence in Jamaica. In May 2010, authorities attempted to arrest and extradite to the United States a powerful Jamaican gang leader and reputed drug trafficker, Christopher “Dudus” Coke. Over the course of 3 days, Jamaican army and police units swept a subsection of the nation’s capital in search of the suspect. Their increased presence was met with hostility by gang-controlled neighborhoods. Over 70 people were killed in clashes and gun battles.

Trafficking-associated violence can reach even more dangerous levels. In Mexico, traffickers frequently battle one another and the state to protect and expand their business. Government officials estimated 9,000 drug-related deaths in 2008, a dramatic upsurge from recent years that has claimed the lives of many bystanders. Mexico has surpassed the 1,000 deaths-per-year benchmark used to designate a state of civil war every year since 1995. This high toll has occurred despite government expenditures of $2.5 billion per year to reduce drug-related violence and fund the deployment of 45,000 troops.

The upsurge in cocaine-related violence in Mexico follows a prolonged period in which cocaine traffic was largely ignored by the state, likely due to successful efforts by traffickers to co-opt officials. Traffickers accumulated much power and influence, and some became de facto authorities in several regions, effectively creating “ungoverned spaces.” When the government eventually confronted traffickers, the groups responded fiercely, revealing that the state no longer held its presumed monopoly on violence and security.

Cocaine traffic has provided a vital financial resource to insurgency groups as well. Recent reports from Peru indicate that the military is encountering resurgent elements of the Shining Path, which apparently has been able to reconstitute itself with proceeds from cocaine trafficking. The 40-year-old Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebel group grew substantially during the 1990s when it began to traffic cocaine. Recently, the FARC diversified its cocaine trade from the United States to Europe by way of West Africa, a presence that could encourage insurgencies in West Africa and facilitate trade in strategies and tactics. According to independent reports, terrorist and armed groups in West Africa’s Sahel region are entering the drug trade.8 The same is true in the Niger Delta, where militias have accepted in-kind cocaine as payment from traffickers.9 This permits a move into the wholesale market and sharply increases revenues.

West Africa today sustains many of the conditions that enabled and fanned narcotics-related violence and conflict in Latin America and the Caribbean. The sub-region hosts many insurgencies and terrorist groups who may view cocaine traffic as a prime opportunity to access financial resources. Likewise, West Africa’s already capable traffickers in small arms, cigarettes, and humans may diversify into cocaine. In Latin America, these problems quickly metastasized into national security challenges, often before the state was able to implement effective responses.

Obstructing Traffic, Protecting Institutions

In 2009, indications of small-scale cocaine processing emerged in Guinea and processing labs were thought to be active in Ghana. This represents a dangerous evolution beyond cocaine transshipment and is further evidence that quick and robust responses are necessary. Lessons drawn from Latin America’s experience offer critical insight into West Africa’s emerging counternarcotics playbook.

Address the Problem Vigorously Now. The threats posed by cocaine trafficking in West Africa are daunting, but they will be much harder to reverse if left unchecked. According to the World Bank, the Caribbean’s rising homicide and crime rates have exhibited “strong inertia effects.” This means that “once crime rates are high, it may be difficult to reduce them. At the same time, crime-reduction efforts in the short term are likely to have huge long-term gains.”10 Since cocaine traffic in West Africa is still maturing, there is an opportunity to prevent its expansion. Deterring cocaine traffic is much cheaper, too. If West Africa can prevent further expansion of traffic, it can avoid the attendant spikes in crime and violence, flight of foreign investment, proliferation of gangs, overcrowded prisons, overburdened courts, and the rising defense and police expenditures seen in Latin America and the Caribbean.

“West Africa today bears many of the conditions that enabled and fanned narcotics-related violence and conflict in Latin America and the Caribbean”

Thus, West African political and civic leaders should strenuously press responsible government agencies to accelerate their counternarcotics efforts. Unfortunately, current indications suggest that recently devised strategies remain unused and poorly distributed. In October 2008, the Economic Community of West African States developed a regional action plan to counter drug trafficking based on five themes: data collection, law enforcement, legal frameworks, drug abuse prevention, and political and budgetary support. The action plan explores specific challenges and identifies aims, strategies, lead agencies, and potential partners for addressing them. However, assessments of country capabilities and needs by the UN Office in West Africa did not commence until November 2009 and only in Liberia and Sierra Leone. The assessments found that many national agencies in Liberia were not even aware that the regional action plan existed.11 That said, the Liberian government’s collaborative work with U.S. authorities led to the extradition of several West African and South American nationals attempting to bribe Liberian officials to facilitate large-scale cocaine transshipments in June 2010.

Safeguard the Integrity of Counternarcotics Institutions. The effectiveness of a government’s ability to marshal resources to prevent and deter threats is, at bottom, a function of public integrity. Advanced training, new military equipment, and other capacity enhancements will have limited effect if institutions and public officials remain corruptible.

“advanced training, new military equipment, and other capacity enhancements will have limited effect if institutions and public officials remain corruptible”

Institutional integrity at even the highest levels of government in Latin America has been compromised by the proceeds of narcotics trafficking. Perceptions of a political-narcotrafficking nexus remain very strong among citizens there, according to studies by the Organization of American States. Recognizing this, West Africa’s leaders should vigorously implement their regional action plan’s recommendation to target “corruption among law enforcement and judicial personnel” as a priority impediment to effective counternarcotics efforts and strengthen oversight bodies, prosecute offending officials, and train state institutions and civil society organizations to monitor and report corruption.

Credible politicians and elections are also vital to public integrity. Accordingly, West African states should devise systems to properly restrict, audit, and, when appropriate, sanction political parties, politicians, and donors who engage in influence peddling. A critical component of implementing such a system is developing the capacity, both within government and among watchdog groups, for forensic accounting so authorities can trace the intricate money trail involved. An immediate and simple reform African states can take is to expand requirements for disclosure of political parties’ and candidates’ financial information such as balance sheets and cash flow statements, measures that have gained widespread support among Latin America’s citizen groups and business community. This disclosure information should be updated regularly and made easily accessible so as to help expose suspicious accumulation of wealth to voters.

Latin America’s experience also underscores the critical importance of protecting judicial institutions. Until recently, Guatemalan criminal groups had extensive influence within government agencies, which they exploited to protect their activities. Murders of uncooperative law enforcement officials were not uncommon. In response, Guatemala’s legislature created an independent International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), which in 2007 was expanded through a partnership with the United Nations. The independent commission detailed jurists from developed and developing countries to work with Guatemalan counterparts to devise legal reforms and protect jurists and judicial integrity. Subsequent reforms to the tax secretariat and penal code helped dismantle illegal groups and identify sources of obstruction to good governance. As a result, 130 individuals have been convicted and 2,000 police officers, an attorney general, and three supreme court justices have been dismissed. One former president has been indicted and another exonerated. Attitudes have since changed and judges, prosecutors, and police officers in Guatemala’s cities and countryside are now more able to do their jobs. The CICIG serves as a possible model in West Africa, whose legislatures should move to create and adequately empower similar commissions partnered with international organizations such as the UN Office on Drugs and Crime or the Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa.

Raise Transaction Costs. Trafficking cocaine through West Africa is comparatively cheap. Make it expensive. Counternarcotics strategies need to focus on raising transaction costs. Arresting traffickers, prosecuting cases, tracking smuggling routes, and undertaking other counternarcotics operations are vital to stemming cocaine traffic. Moreover, efforts that merely hinder the business of moving cocaine through West Africa make it more arduous, expensive, and unappealing to traffickers. The more expensive it is, the less inclined cocaine traffickers will be to use West Africa as a transit route.

Operations that amount to no more than harassment have produced impressive results in the Carib- bean. From very low levels in 2000, annual cocaine seizures in the Netherlands Antilles reached 9 tons by 2004. To counter rising traffic, Antillean and Dutch airport security officers stepped up searches of arriving and departing passengers. But, rather than arresting offenders (the low-level mules), police offered them the opportunity to cooperate. If mules were carrying less than 3 kilograms of drugs, they were not arrested but were returned to their point of origin and given receipts explaining the drug seizures so they would not face retribution from their employers. This tactic raised the cost of transporting drugs through the Antilles. Meanwhile, the number of mules transiting the Netherlands Antilles dropped 96 percent.12

Efforts to raise costs do not solely entail interdiction. Nicaragua has had great success reducing the labor supply for cocaine trafficking through its youth engagement strategy, which offers occupational alternatives, specialized corrections programs, and rehabilitation for former gang members. The National Police also work with partners in government, the media, the private sector, and civil society to implement a Prevention of Juvenile Violence program. This initiative has stymied the expansion of Central America’s large transnational gangs, which play critical roles in transshipment. While gang members in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala number in the tens of thousands, Nicaragua’s tally dropped from 8,500 in 1999 to 4,500 by Nicaragua’s success comes despite its lower per capita income relative to its neighbors. Drug trafficking is still a problem for Nicaragua, but a country with limited resources can apply novel approaches to hamper narcotics trafficking.

The corrosive influence of narcotics trafficking across Africa threatens to become institutionally entrenched and poses severe and persistent security challenges. Such has been the case in many parts of Latin America and the Caribbean, even where narcotics production and abuse have remained low. Applying these lessons will help Africa minimize the debilitating effects of this trade and the risks it poses to the continent’s recent governance, economic, and stability gains.

Notes

- ⇑ Alan Doig and Stephanie McIvor, “National Integrity Systems Country Study Report: Jamaica 2003,” Transparency International, 51.

- ⇑“I’m Not a Cocaine Baron,” Daily Guide, April 21, 2010; Stephen Ellis, “West Africa’s International Drug Trade,” African Affairs (2009), 192.

- ⇑ “‘Cocaine Smuggling’ Nigerian Politician Held in Lagos,” BBC, May 17, 2010.

- ⇑ Tanu Jalloh, “Kemoh Sesay Sacked for Police to Arrest,” Concord Times, August 5, 2008.

- ⇑ For reports from Benin, Ghana, and Nigeria, respectively: “Screening Out Morally Unfit Crime Fighters,” UN Integrated Regional Information Network, October 29, 2008; Emmanuel Akli, “MV Resurrected Benjamin Cocaine Affair,” Ghanaian Chronicle, April 21, 2010; Idowu Sowunmi, “Funding, Operational Problems Cripple NDLEA,” This Day, November 28, 2009.

- ⇑ William C. Prillaman, “Crime, Democracy, and Development in Latin America,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2003, 15.

- ⇑ World Bank, “Crime, Violence, and Development: Trends, Costs, and Policy Options in the Caribbean,” March 2007, i.

- ⇑ UN Office on Drugs and Crime, “Security Council Debates ‘Devastating Impact’ of Drug Trafficking,” December 9, 2009.

- ⇑ Mike McGovern, “Confronting Drug Trafficking in West Africa,” testimony before the Subcommittee on African Affairs, U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, June 23, 2009. See also Ellis.

- ⇑ World Bank, 33.

- ⇑ “Report of the Secretary General on the United Nations Office for West Africa,” United Nations Security Council, December 31, 2009, 11.

- ⇑ World Bank, 98.

Davin O’Regan is a Research Associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.