Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Despite numerous peace agreements, Africa’s Great Lakes region has been in a persistent state of conflict for the past two decades. The contributions and shortcomings of some of the most significant previous peace initiatives, however, offer vital lessons as to how to mitigate the local level tensions, national political dynamics, and competing regional interests that have led to recurring outbreaks of violence.

Highlights

- Conflict in Africa’s Great Lakes region persists because of a complex mixture of regional politics, financial incentives, ethnic polarization, and weak and illegitimate governance.

- Previous peace agreements have made important contributions to stability but have only been partly successful because they have not addressed some key conflict drivers.

- Given the regional nature of the instability, international actors, especially those in Europe and the United States that provide significant financial support to governments in the Great Lakes, are vital to achieving a comprehensive settlement.

Landmark peace agreements signed in 2002 by 11 African governments and various nonstate armed groups were meant to end 7 years of war that had ravaged Africa’s Great Lakes region. A decade later, instability, tightly intertwined with regional geopolitics, persists. Recurring conflict has killed tens of thousands, mostly civilians, and displaced millions of others. The extended instability has also led to a collapse of basic social services and economic activity in parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), resulting in manifold more deaths due to malnutrition, lack of access to basic healthcare, and scarce livelihood opportunities.1 Amid this breakdown, barbaric forms of violence have emerged. During one 4-day period in the summer of 2011, nearly 400 women, men, and children were raped by militia fighters. Since 1996, there have reportedly been more than 200,000 rapes, which are mostly attributed to armed militias.2

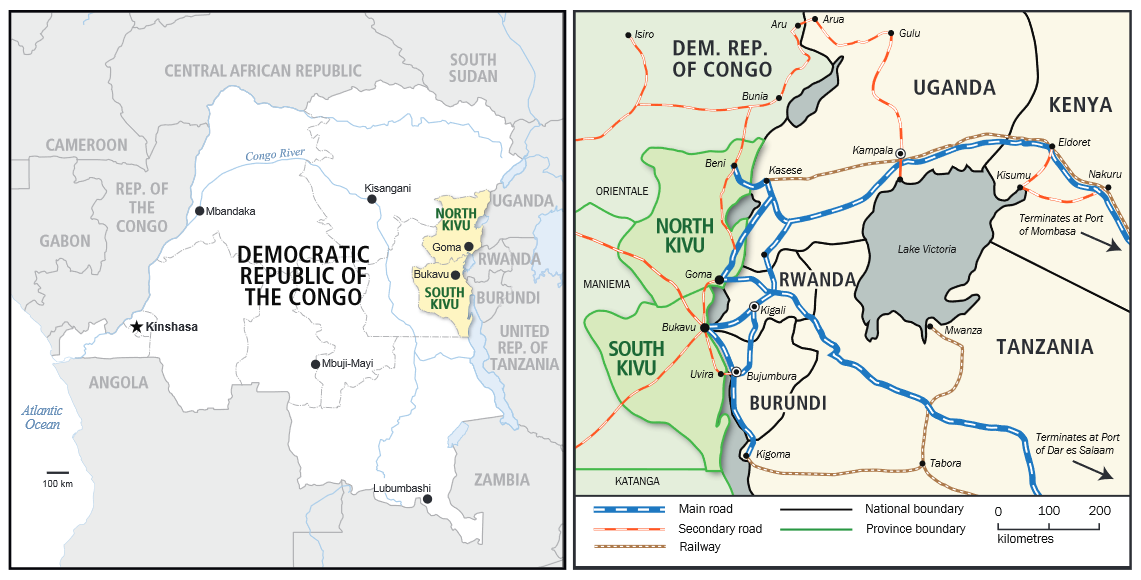

The provinces of North and South Kivu in the eastern DRC have been the epicenter of the fighting (see map). They are the largest source of recruits for a constantly shifting mix of militias. By one count, there are at least 19 nonstate militias comprising 7,000 to 17,000 fighters in the Kivus.3 Typical of the splintering seen in other extended conflicts, United Nations (UN) peacekeeping officials warn of a further “mushrooming of new groups.”4 Many of these groups are criminally oriented militias seeking to profit from trafficking the region’s natural resources. Some are led by local politicians and others are community self-defense forces. Alliances, goals, and leadership among these groups are often temporary, opportunistic, and at times contradictory.

Conflict in the Kivus also has powerful external drivers. Militias opposed to the governments in Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda are based in the Kivus. In response, these countries have deployed troops and sponsored militias in the eastern DRC, feeding the proliferation of armed groups. Nearly all of the illicit traffic in Congolese minerals that funds armed groups transits Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda.

Source: “The Role of the Exploitation of Natural Resources in Fuelling and Prolonging Crises in the Eastern DRC,” International Alert, January 2010, 79. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Both maps modified by author.

Despite numerous initiatives and agreements, no comprehensive framework to end this complex conflict has been forged. Rather, international engagement has continued to be fragmented with an emphasis on symptoms. Costs to the international community in peacekeeping and humanitarian assistance alone total more than $2 billion annually. The persistent state of crisis, similarly, constrains economic investment in Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda. Instability in the Great Lakes, moreover, hinders other security challenges in the region, including statebuilding efforts in South Sudan and defeating the Lord’s Resistance Army militia.

Entrenched Regional Conflict

As part of its effort to consolidate control over post-genocide Rwanda, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) launched an operation into the eastern Congo in 1996. The RPF aimed to neutralize the remnants of the former Rwandan regime’s military, the Forces Armées Rwandaises (FAR), and the Rwandan Interahamwe militia who were key actors in the Rwandan genocide. These fighters, who numbered in the tens of thousands, had fled to the Congo where they enjoyed free maneuver and launched raids into Rwanda.

Soon after the initial operations the RPF broadened its goals to remove the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko, president of then Zaire, whom they saw as protecting their enemies. Several other countries, including Burundi and Uganda, eventually provided frontline troops and support to build a Congolese rebellion, ostensibly led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, known as l’Alliance des Forces Démocratique pour la Libération du Congo-Zaire (AFDL).5

Kabila assumed power in Kinshasa in May 1997 after Mobutu’s disorganized forces were quickly defeated during a 7-month war of “liberation.” However, lacking legitimacy, geopolitical vision, and governance experience, his regime was characterized by brutality and fecklessness. Concerned that this arrangement would reenergize the ex-FAR in the eastern DRC, Rwanda launched a second invasion, the so-called “war of occupation” from 1998 to 2003, and established another militia, Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie (RCD). Kabila, meanwhile, urged the ex-FAR, his erstwhile enemies, to join his government in fighting the RPF. In response to this second Rwandan gambit, seven other African armies deployed to the DRC either to counter or support the Rwandans. Kabila was assassinated in January 2001 by members of his presidential guard and was succeeded by his son Joseph, who led a government based on a transitional power-sharing arrangement negotiated in 2002. Most foreign armies subsequently withdrew in 2003.

Rwanda’s 1996 invasion of the eastern Congo set a pattern of conflict that has since repeated itself and, in effect, wholly shifted Rwanda’s previous civil war onto Congolese soil. Its reliance on proxy militias in the DRC and periodic military operations to resolve complex political challenges prompted other governments to follow suit. This has led to the proliferation of armed nonstate groups and instigated a never-ending series of crises in the region.6 In recent years, the key actors have been the Congrès National Pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP), a militia supported by Rwanda, and the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), which is composed of ex-FAR leaders and poses a security risk to Rwanda.

A lasting solution to the fighting in the Great Lakes will take more than the end of the FDLR and CNDP, however. Years of fighting have spawned other conflict drivers and peace spoilers. Among them are the eastern DRC’s easily accessible natural resources, particularly gold, tin, colombite-tantalite (coltan), and tungsten. Armed groups depend on revenues from the illicit trade in these resources. For some, it has become a primary objective. The same holds true for elements of the Forces Armées du République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC), the DRC’s national army, which have been implicated in mineral trafficking.7

The minerals trade also features prominently in decision-making in Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda. Most of the eastern DRC’s minerals must move through these and other East African countries, where they are levied with fees and re-exported, often by local businesses. This has become a significant source of economic activity and growth. For example, Rwanda’s domestic minerals production is small, but the mining sector was a “key growth engine” for Rwanda in 2011 during a year of otherwise subdued regional economic activity, including a slump in Rwanda’s agricultural sector.8 In March 2012, the firm Africa Primary Tungsten—one of Rwanda’s largest taxpayers—was censured by an international mining association after evidence emerged that it was misrepresenting the origin of its minerals.9 In short, powerful business and government interests profiting from the instability in the DRC have incentives to keep the conflict going.

The invasions of the DRC have also catalyzed tensions at the community level. After the RPF’s military victory in Rwanda in 1994, nearly 2 million refugees from Rwanda’s Hutu community, including leaders of the Rwandan genocide, crossed into the eastern Congo, altering the region’s demographic composition. The RPF’s tactic of arming various Tutsi-dominated militias has likewise fostered mistrust of the DRC Tutsi community. In response to the heightened polarization and militarization of the region, communities—including the Nande, Nyanga, Tembo, Hunde, Shi, Rega, Bembe, and others—created armed militias, known locally as Mai-Mai, to defend themselves.

Decades of cross-border migration combined with ongoing conflict-related displacement of 1.4 million people in the Kivus have also turned the already thorny issue of land ownership into a major challenge. With each crisis, property belonging to locals was occupied by new arrivals. Any attempt to recover or return to this land became an intercommunal casus belli. The Kivus have among the highest population densities in the DRC, with nearly 70 inhabitants/km2 compared with a national average of 29 inhabitants/km2. The resulting weakening of traditional authorities coupled with the government’s inability to enforce property laws have produced a state of permanent conflict over land ownership.

Conditions in the DRC’s neighbors also feed the proliferation of armed groups. In Burundi, the government has been accused of human rights violations, including extrajudicial executions by the army. In response, the previously demobilized Forces Nationales de Libération (FNL) rebel militia has regrouped and rearmed in South Kivu. A new rebellion, Fronatu Tabara, has also based itself in South Kivu. This has stoked fears that violence may return to Burundi in full force and engulf the eastern DRC.

In Rwanda, a minority elite is consolidating a monopoly of political and financial power and is intolerant of opposition voices. Arrests of activists and independent journalists are common. The post-genocide legal system has also been tainted by corruption and procedural irregularities,10 hindering the disarmament of the FDLR and the return of tens of thousands of refugees from the DRC.

Meanwhile, hamstrung by weak legitimacy and capacity, the DRC government has had little success in extending its authority in the Kivus. Evidence that the November 2011 elections in the DRC were deeply flawed, including systematic intimidation and violence against voters by security forces, has fueled mistrust of the government and diminished its ability to mitigate the conflict. Frustrated citizens are turning to CNDP breakaways, the Mai-Mai, and other groups to protect their interests.

Gains and Shortcomings of an Incomplete Peace Process

A dozen major peace agreements, negotiations, and reconciliation initiatives, often brokered with help from the international community, have been the primary vehicles employed to resolve conflict in the Great Lakes region.11 Most of these accords, however, have addressed only some of the causes and consequences of the conflict and, at times, neglected its principal drivers.

ICGLR approach

The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) has to date been the largest peace initiative. Convened by UN Resolution 1291 in 2000 and held under the auspices of the African Union and UN with support from international donors, it brought 18 countries to the negotiating table, 11 of which were directly involved in the conflict. After 6 years of political negotiations, the conference gave rise to the Pact on Security, Stability, and Development in the Great Lakes Region, signed in December 2006 by heads of state from Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the DRC, Kenya, the Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. The pact entered into force in June 2008 after it was ratified by eight signatories. An ICGLR Secretariat was established in Bujumbura to implement the pact’s 10 protocols, including regional non-aggression and mutual defense, good governance, and reconstruction and development. Only limited progress toward these objectives have been realized to date, however.

A key contribution of the ICGLR has been that it took into account the economic dimensions and motivations of the conflict in the eastern DRC. Specifically, it launched a Regional Initiative on Natural Resources to certify, formalize, and track the minerals trade so as to eliminate trafficking and the role of armed groups. Pilot schemes in Rwanda and South Kivu have shown some progress.12

The ICGLR’s main shortcoming has been that it did not address the massive human rights violations committed by various state actors that intervened in the DRC—abuses that have now been well documented through UN reports.13 As a consequence, these actors have had little incentive to end their reliance on short-term military responses and proxy militias to meet their immediate security and economic interests.

The Tripartite Plus Commission

The Tripartite Plus Commission was a U.S. initiative launched in 2004 dealing mainly with the FDLR presence in the DRC. This initiative culminated in a joint communiqué on November 9, 2007, committing the DRC and Rwandan governments to “a common approach to address the threat posed to their common security and stability by the ex-FAR/Interahamwe.” The Nairobi communiqué fulfilled a fundamental aim of the Rwandan Defence Forces (RDF) to more aggressively target the ex-FAR remnants that comprise the FDLR.

The FARDC-RDF collaboration has been very unpopular in the eastern DRC, even though many in the region dread the FDLR. The joint operations resulted in many civilian casualties and disarmed few FDLR, who have later conducted reprisal attacks against villages accused of aiding the FARDC and RDF. President Kabila is also paying a price for his expansion of military operations in the eastern DRC. In 2006, he received 95 percent of the vote in South Kivu and 78 percent in North Kivu, largely because he promised to bring an end to the Rwandan presence and restore peace. In the 2011 elections he garnered just 45 and 39 percent, respectively, in the same provinces. Given widespread electoral irregularities, his actual support may be even lower. His options and ability to manage the conflict will shrink further if he continues to lose support in the east.

The Tripartite Plus’s main achievement was to bring the two major antagonists—the Rwandan and Congolese leadership—to the table. Indeed, the U.S. Government extended much effort to force the two enemies to talk to one another, no doubt drawing from its extensive relations with and support to both governments. Donor support accounts for 40 percent of Rwanda’s annual government budget.14 Improving relations between Rwanda and the DRC is critical to consolidating peace throughout the entire subregion, and this approach showed that constructive communication is possible.

This agreement errs in limiting responsibility for the instability to the FDLR. When the DRC government once suggested that illicit minerals trafficking be discussed within the Tripartite Plus arrangement, the Rwandan and Ugandan governments declined, indicating that this was not a regional issue.15 Moreover, the Tripartite Plus agreement stipulated that the DRC must offer the FDLR a choice between either voluntarily returning to Rwanda without security guarantees or being relocated and dispersed throughout the Congolese territory. If they accepted neither of these proposals, they faced military operations by the FARDC and RDF.

This narrow approach ignores a UN assessment that at most 2,500 of the remaining 70,000 Rwandan refugees in the DRC are combatants.16 Beyond joint military operations, then, cooperation on refugee protection, repatriation, and resettlement could relieve local-level tensions and minimize a pool of potential FDLR recruits and supporters. Nor can the peace process in the DRC be separated from the broader context of democratization in the Great Lakes region. Refugees in the DRC from Burundi and Rwanda will continue to resist returning to a country where they face a restrictive political environment. The Tripartite Commission’s initiatives, thus, lacked the confidence-and trust-building elements essential for successful disarmament.

Goma Conference

The Goma peace conference has been the only one initiated by the DRC government. From January 6–24, 2008, the conference brought together 1,500 delegates from all communities and social strata in North and South Kivu. Its general objective was to rally stakeholders and involve them in the restoration of peace in the area. Delegates ultimately signed an Acte d’engagement to cease hostilities.

By giving all communities and most armed groups a voice, the Goma conference represented a significant step forward in understanding the conflict from local perspectives. And a high priority for these communities was to prevent those guilty of committing massacres, sexual violence, or inciting ethnic hatred from holding positions of responsibility, particularly in the security services.17 After the conference, the involvement of traditional village chiefs and other community leaders facilitated the disarmament or integration of 22 armed groups into the national army—indicating a strong desire at the local level to end the fighting. The FDLR were excluded from the Goma conference, however.

The Goma conference defused tensions in the Kivus, but months of heavy fighting began in August 2008 between the CNDP and FARDC, jeopardizing the commitment of other signatories to disarm. By the end of the year, the CNDP was poised to capture Goma, the capital of North Kivu. Hundreds of civilians were killed and hundreds of thousands displaced.

The fighting finally ebbed when, in a surprising turn of events, Laurent Nkunda, then leader of the CNDP, was arrested by authorities in Rwanda in January 2009. According to some accounts, Nkunda’s sponsors in Rwanda began to worry that he was growing unreliable and unresponsive, and therefore they moved to shuffle the leadership in the CNDP. Rwanda was also likely motivated by growing international criticism of its support to the CNDP.

A Lasting Solution

To date, peace initiatives to end armed violence in the Great Lakes have addressed only some of the causes and consequences of the conflict. A multipronged framework drawing from lessons of previous agreements can rebalance future peace efforts to achieve sustainable solutions to the conflict.

End support to proxy militias.

Among the core group of states involved in the conflict, all have supported a proxy militia. This tactic is often intended to manage valid national security threats, but tends to be a counterproductive expedient that precipitates larger crises. In the end, most benefactors lose control over these proxies. These groups transform and develop their own agendas, sometimes threatening the very interests they were intended to protect. The AFDL, RCD, and CNDP all exemplify this pattern.

Rwanda, in particular, must end its support to these groups. Its actions in the DRC undermine the regional stability needed to attract further international investment. At stake, by extension, is its standing with international donors and investors.

For its part, the government of the DRC must meet its obligations to disarm or integrate militias within the FARDC. Its failure to sustain its engagement following the consensus achieved during the Goma conference encouraged groups to pull out of the process and contributed to the 2008-2009 crisis in the Kivus. At times, it has also pursued temporary alliances with some militias, including the FDLR, to target others. It should rather prioritize security through community partnerships, achieving disarmament by demonstrating its trustworthiness, and the progressive isolation of recalcitrant combatants. A particular focus should be the senior leaders of the FDLR, both to address Rwanda’s legitimate concerns but also because the FDLR has been a severe threat to communities in the Kivus. Unfortunately, after years of seeing its numbers and maneuverability slowly shrink, the FDLR enjoyed a resurgence in 2012. Fighting in the Kivus between the FARDC and another Rwandan supported militia called M23 provided the FDLR some breathing space in which to recruit and conduct new attacks.

International partners will need to apply more pressure on governments that undermine the peace process through their support of militias. The United States, the United Kingdom, and European Union provide substantial budgetary assistance to governments in the Great Lakes, and therefore should ensure that such support does not go to countries working at cross purposes. Likewise, international partners should provide support to uphold efforts to disarm, demobilize, or integrate combatants.

International engagement should not stop there, however. Militia leaders and their state sponsors who persist in undermining stability in the DRC should face International Criminal Court (ICC) investigations on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including systematized murder, rape, torture, recruiting of child soldiers, and pillaging. Currently, General Bosco Ntaganda, formerly of the CNDP and now a head of M23, faces an ICC arrest warrant. Major General Sylvester Mudacumura of the FDLR is also under ICC investigation. General Laurent Nkunda, the former head of the CNDP under house arrest in Rwanda, and Colonel Sultani Makenga, an M23 commander, should likewise face ICC investigations for their involvement in unsolved massacres and recruiting child soldiers. Providing weapons and ammunition to the FDLR, M23, and for other military activities in the DRC, moreover, contravenes a United Nations Security Council arms embargo. Accordingly, other FDLR figures in the Diaspora could face charges and investigations, such as Ignace Murwanashyaka, an FDLR political leader and fundraiser on trial for war crimes in Germany. Likewise, top Rwandan officials, including Minister of Defense James Kabarebe, have been identified by the UN as having provided troops, ammunition, and weapons to M23.18

Develop political space as alternative to militancy.

Ever since the 2007 Nairobi communiqué, military responses to the conflict have been prioritized at the expense of other approaches. The results have been very mixed. Groups targeted in sweeps often relocate until operations end, then return and attack civilians whom they accuse of helping state authorities. Military operations against nonstate armed groups may be necessary, but they should be combined with initiatives that offer an alternative and a future to certain members of these groups, especially those not guilty of war crimes.

There is reason to believe that combatants can be persuaded to stand down. The Goma conference kindled some confidence among militia groups on a way forward. Likewise, during previous negotiations, the FDLR agreed to renounce the use of force, condemn genocide ideology, cooperate with the international tribunal on the genocide, and transform itself into a political party in Rwanda.19 Offering members of militias reasonable and secure opportunities in their home countries should be a key aspect in peace efforts. Fostering protection of political rights and civil liberties, moreover, will undermine the claims of exclusion and persecution that militias such as the FDLR use to recruit among exile communities.

Ensure local community representation.

Local communities in the Kivus are most exposed to the ongoing conflict in the region. Many members of these communities work in the artisanal mines that fuel much of the fighting and some, lacking suitable alternatives, make a living as professional militants. As a result of the lengthy conflict, land disputes, ethnic tensions, and other intercommunal challenges have worsened. Accordingly, the local communities of the Kivus need to be integrated into any framework for peace in the DRC.

As the Goma conference demonstrated, including local community representation in the peace process can build consensus, reduce militia activity, and support disarmament. Future follow-on initiatives should be pursued, but with critical adjustments. Leadership from the Congolese state is essential to reduce the multiple parallel administrative systems that currently contribute to weak governance in the Kivus. Given the intercommunal tensions that have developed during years of conflict, regular meetings and accessible mechanisms through which community representatives can channel concerns to responsive government officials will be critical to breaking the reliance on militias and violence. Land tenure as well as displacement and relocation matters should be priorities. Finally, given the overriding regional political and ethnic dimensions to the instability, strong external engagement and pressure will be crucial to ensure that the Congolese state meets its obligations and earns the confidence of communities and combatants.

Regulate the minerals sector.

Illicit mineral trafficking is currently a key driver of conflict in the eastern DRC. However, it can also be a means of cooperation and collaboration. The mining sector has numerous stakeholders, from artisanal miners in the Kivus to influential politicians and businessmen in the capitals of the DRC, Rwanda, and elsewhere. None can afford to see it shrink and most would like to see it expand. Enhancing the transparency and regulation of this trade will help it grow, thereby benefiting all. It would increase tax, customs, and other earnings for the DRC as well as in Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda, which will remain the most viable export routes for these goods. A more properly regulated sector would attract more investment, creating new opportunities for communities in the Kivus.

States in the subregion should continue to expand the progress achieved in establishing mineral supply chain verification systems under the ICGLR process. Particular attention should be paid to improving the transparency of gold mining, as illicit trafficking of gold remains widespread and a key source of funding for armed groups. New U.S. laws that require companies to ensure that minerals sourced from the Great Lakes are “conflict free” have also fostered new impetus to improve the security situation. Several consumers of the region’s minerals have already begun to seek alternative sources. If countries in the region wish to maintain, let alone expand, the customer base for the region’s resources, they must collaborate to reduce the size and number of militias in the Kivus.

Conclusion

The prospects for peace in the DRC will fundamentally depend on the development of an inclusive approach that combines the security and economic interests of the various local and regional actors in the Great Lakes. A fire cannot be extinguished without bothering to identify the arsonist, understand his in tentions, ascertain his plan and his methods, or institute measures to ensure he does not repeat his crime.

Moreover, none of this work can succeed without a sustained effort to rebuild a functioning, legitimate state in the DRC.20 At the end of the day, it is up to the Congolese to assume leadership over their territory so as to ensure security in the Great Lakes.

Rigobert Minani Bihuzo S.J. is the Director of the Jesuit Africa Social Centers network and was Director of the political section at the Center of Study for Social Action in Kinshasa. He has participated in several peace negotiations in the Great Lakes.

Notes

- ⇑ Benjamin Coghlan et al., “Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An Ongoing Crisis,” The International Rescue Committee and the Burnet Institute, 2007.

- ⇑ Report of the Panel on Remedies and Reparations for Victims of Sexual Violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Geneva: Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, March 2011).

- ⇑ Jason Stearns, “List of Armed Groups in the Kivus,” Congo Siasa, June 9, 2010.

- ⇑ Jason Stearns, “New Armed Groups Appear in South Kivu,” Congo Siasa, September 15, 2011.

- ⇑ Report of the Mapping Exercise Documenting the Most Serious Violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law Committed within the Territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between March 1993 and June 2003 (Geneva: Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, August 2010), 70.

- ⇑ Final Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (UN Security Council: S/2008/773, December 2008).

- ⇑ Ruben de Koning, Conflict Minerals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Aligning Trade and Security Inverventions, SIPRI Policy Paper No. 27 (Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, June 2011), 17-18.

- ⇑ Resilience in the Face of Economic Adversity: Policies for Growth with a Focus on Household Enterprises, Rwanda Economic Update 2nd Edition, (Washington, DC: World Bank, November 2011), 3.

- ⇑ Ivan R. Mugisha, “Firms Blacklisted for Illegal Mineral Tagging,” New Times (Kigali), March 7, 2012.

- ⇑ Justice Compromised: The Legacy of Rwanda’s Community-Based Gacaca Courts (New York: Human Rights Watch, May 2011).

- ⇑ Jean Migabo Kalere, Textes fondamentaux sur le processus de paix en RDC (Leuven: CPRS, 2008). Rigobert Minani Bihuzo, S.J., Du pacte de stabilité de Nairobi à l’Acte d’engagement de Goma : Enjeux et défis des processus de paix en RDC (Kinshasa : Cepas/Rodhecic, 2008).

- ⇑ Shawn Blore, “Project Review: Implementing Certified Trading Chains (CTC) in Rwanda,” German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, March 2011.

- ⇑ See notes 2, 5, 6, and 19.

- ⇑ World Bank.

- ⇑ Morten Bøås, Randi Lotsberg, and Jean-Luc Ndizeye, “The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) – Review of Norwegian Support to the ICGLR Secretariat,” Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, June 2009.

- ⇑ “Over 1800 FDLR Armed Rebels in DR Congo Surrender to UN Peacekeepers in 2010,” UN Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, February 3, 2011. UNHCR Statistical Online Population Database.

- ⇑ Laura Davis, Justice-Sensitive Security Sector System Reform in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Brussels: Initiative for Peacebuilding, 2009), 11.

- ⇑ Addendum to the Interim Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (UN Security Council: S/2012/348, June 2012). “Rwanda Should Stop Aiding War Crimes Suspect,” Human Rights Watch, June 4, 2012.

- ⇑ FDLR Declaration (Sant’Egidio peace talks between the FDLR and the Government of the DRC, Rome, Italy, March 31, 2005).

- ⇑ Rigobert Minani Bihuzo, 1990–2007, 17 ans de transition politique et perspective démocratique en RDC (Kinshasa : Cepas/ Rodhecic, 2008).